Sources: webpage and Lunapic

1. THE AUTOCRACY AND THE PROLETARIAT.

Under the pressure of workers and radical youth the liberal gatherings become open public meetings and street demonstrations.1

[...]

Autocratic Russia has already been defeated by constitutional Japan, and dragging the war on will only increase and aggravate the defeat. The best part of the Russian Navy has been destroyed; the position of Port Arthur is hopeless and the naval squadron sent to its relief does not have the slightest chance of even reaching its destination, let alone success; the main Army under Kuropatkin has lost over 200,000 men and stands exhausted and helpless before the enemy who is bound to crush it after the capture of Port Arthur. Military disaster is inevitable and discontent along with it, the unrest and indignation will increase tenfold inevitably.

2. THE FALL OF PORT ARTHUR.

The Russian people benefit from the autocracy's defeat. The capitulation of Port Arthur is a prologue to the capitulation of tsarism.1 The war is not yet finished by far, but its continuation increases the unrest and discontent of the Russian people immeasurably, it brings the hour of a new great war nearer, the war of the people against the autocracy.

3. THE FALL OF PORT ARTHUR.

The Russian fleet of the Pacific is condemned to impotence. The Japanese are the masters of the sea and so they continue their land invasion. They have won the first round. Although two important vessels have been lost, Petropavlosk and Varyag, Admiral Skrydlov may count, after repairs, on a fleet of six battleships, four heavy cruisers, four regular cruisers, two fast light cruisers, two heavy torpedo cruisers and more than twenty torpedo boats. When all the repair work is done and Baltic Fleet reinforcements arrive, the naval balance of power will reverse completely. The Japanese realize this, so they will try to smash the Pacific Fleet as quickly as possible.

A Russian Navy officer recently arrived to Vladivostok recounted the following geste witnessed in one of the many naval duels fought on the waters off Port Arthur, a geste that reveals the Japanese soldiers' self-denial and the patriotism they exude in the hour of trial.

"I think the date was March 14...I don't recall. Our torpedo boats had encircled a Japanese one which, knocked out and set to go under at any moment, had no means of averting disaster. The crew could have saved themselves by swimming toward the Japanese fleet that was coming to their rescue. Ours, inferior in number and strength, was heading back to Port Arthur's bay.

"The Japanese crew stayed at their posts and as the torpedo boat began to slowly submerge, its deck protruding above the water a few centimeters, came out to the railing the commander, a pudgy mean-looking fellow, extracted a cigarette from his pouch and lit it with the utmost nonchalance conceivable.

"Moments afterward the torpedo boat went under amidst its sailors' shouts of joy, who escorted it to the bottom of the sea to meet their common sepulchre beneath the waters of the Pacific Ocean."

War is for the Japanese a sort of ritual suicide offered to the divinity as a placating sacrifice.

Eight Russian torpedo boats managed to breach the naval blockade during the night of August 18 and reach the open sea.

[...]

General Stessel's order of the day for August 13 read:

Bold defenders of Port Arthur: The moment has come to regroup our forces and defend this piece of Russian territory, the fortress of Port Arthur. Our great Czar and our common mother—the Russian motherland—expect us to do our sacred duty without reservations: the defense of the outpost against the enemy's onslaught. Let every one of us remember the words of our sacred oath and steep his heart with the notion that there is no place for him other than his assigned place on the fortress bulwarks. Faithful to the example of our forefathers we shall not retreat one step, we will not cede anything to the foe and we shall fight him with courage and resolve. We will make the enemy pay for his impudent aggression; let those infidels know that God is with us.

The Argentinian colonel who monitors Japanese operations has declared that the Russian defensive works are admirably built.

When forts "Rhiungshan" and "Kikushan" are captured the Japanese will virtually control the sector housing the railway line to Port Arthur. These two forts together with the majority of the 54 which encircle the city have armoured ramparts of steel 6 inches thick, provided with openings for the rapid-fire canons; these canons have wreaked more havoc in the Japanese lines than even the land mines have. On top of multiple means of defence the Russians electrified their barbed wire fences. Since August 31 it may be said that there is no fighting on this sector. The Japanese shell it every morning when the sun shines at full strength and the Russians reply in the afternoon when the sun is on their side. Japanese casualties over the past five weeks are estimated to be 20,000.

The Japanese man sharing this information says that publishing it poses no inconvenience because the Russians are perfectly acquainted with their adversaries' game plan.

London: A British flotilla of 50 fishing boats was ploughed under by Russia's Baltic fleet (sailing at full steam toward Port Arthur). Several British boats sank with the loss of all men. Several others were seriously damaged, many sailors were injured. The newspapers demand the declaration of war on Russia, branding it a pirate nation.

During the Crimean War a brave Russian admiral pleaded with his superiors to be granted leave to attack the Allies' naval forces in circumstances of certain victory. His plea was refused. The Russian vessels were scuttled and the sailors remolded into soldiers. "The Army shall defeat the enemy," it was then said in Crimea.

Now, after a lapse of fifty years, the same error has been repeated on the Liao-Tung peninsula.

The Russian warships sheltering in Port Arthur were let be exterminated in the harbour, like mice in their nest, instead of boldly putting out to sea with the mission of inflicting maximum harm on the enemy even at the risk of getting sunk. The Russians sacrificed their vessels blindly in order to deploy the ships' canons and crews on land.

Over the past few days nothing would have impeded Viren from attempting to lead his fleet to Vladisvostok, even bartering an encounter with Togo, to whose navy he could have done substantial harm, inflicting such losses as Rozhestvensky would have profited from upon his arrival to Far East waters.

Mr. Fred T. Jane the famous English naval critic says in the Daily Chronicle that if a trace of common sense remains in the Czar's court the order will be given to the Baltic armada to return to Libau immediately in order to avert the unavoidable disaster which awaits her.

The critic's comments about Russia are cruel,

The moral of the destruction of Port Arthur's fleet is that Russia has absolutely deserved the inevitable final catastrophe for having overlooked the most elementary principles of war.

Stessel will perhaps prolong the resistance ad infinitum. No matter! The Japanese will seek to subdue the garrison by starvation if they don't vanquish it through frontal assault.

After the Baltic armada is annihilated Port Arthur will fall like ripe fruit hanging from a tree.

Stessel will be the hero to console Russia of her defeat when the war ends. An intelligent sovereign would instead have him put in bonds for not realizing that the key to victory lay in mastery of the sea.

Stessel in his magnificent blend of bravery and stupidity has inclined the balance in favour of the Japanese, who will owe their victory entirely to him.

Mr. Jane's criticism is plainly excessive but understandable because he always had incontestable faith in the Russian Navy and he expressed it publicly on several occasions.

In addition he is not inured to the prejudices inbred in British mariners against land armies. Still it is incumbent to grant that a considerable serving of truth comes with his peppery assertions.

4. "OUR FATHER THE TSAR" AND THE BARRICADES.

The first day of the Russian revolution brought the old Russia and the new Russia face to face with startling force and witnessed the death agony of the peasants' age-old faith in "Our Father the Tsar" and the birth of a revolutionary people, the urban proletariat. No wonder the European bourgeois newspapers say that the Russia of Old Style January 10 is no longer the Russia of Old Style January 8. No wonder the cited German Social-Democratic newspaper recalls how seventy years ago the working-class movement started in England—how in 1834 English workers held street demonstrations to protest the banning of trade unions, how in 1838 they drew up a "People's Charter" at monster meetings near Manchester and how Parson Stephens proclaimed "the right of every man that breathes God's free air and treads upon God's free earth to have his home and hearth." And the same parson called on the assembled workers to take up arms.

Here too in Russia a priest found himself at the head of the movement. One day he called for a march with a peaceful petition to the tsar himself and the next day he issued a call to revolution.

"Comrades, Russian workers!" Father Georgi Gapon wrote after that bloody day in a letter read at a meeting of liberals, "We no longer have a tsar. Today a river of blood separates him from the Russian people. It is time for Russian workers to begin a struggle for the people's freedom without him. For today I give you my blessing. Tomorrow I shall be with you. Today I am busy working for our cause."

5. BLOODY SUNDAY (Old Style January 9, 1905).

Extremely serious incidents in St. Petersburg yesterday (January 22). Thousands of striking workers in an attitude "not at all peaceful" headed to the Winter Palace. The military unit guarding the palace dispersed them using blank cartridges. The workers regrouped on the banks of the Neva River and returned. The imperial troops then reloaded with regular cartridges and fired. The combat was "formidable" requiring the use of Cavalry against the demonstrators, who shot back. Pope Gapon was hurt. Many dead and wounded.

New Details. Early clusters of workers appeared in front of the Winter Palace at 10:00 AM. At 12:00 midday others started to congregate on the bridges. Disorders were taking place simultaneously in front of the Winter Palace.

Dead and wounded at the Arsenal. The revolutionaries carried revolvers. Workers looted the Arsenal. The Red Cross took the wounded away in sleighs to hospitals and pharmacies.

The soldiers and the people. Many soldiers dropped their guns because, they said, they did not want to murder the people. Forces loyal to the Czar chased after them.

Into the Neva. The people crowding Alexander Bridge jumped off into the river upon seeing themselves besieged by Cossacks.

Reason for the assault. A leader of the sedition declared they had assaulted the Palace because the Czar refused their demands.

LAST HOUR. The news about the bloody events of St. Petersburg are terrifying. Troops charged thousands of strikers mercilessly. These did not put up any resistance and let themselves be killed. The workers acclaimed the Czar's army commanders as they marched forward. The snowy streets are stained with blood.

Inciting them to vengeance. Around 10,000 strikers gathered near the Workers Union. Their leaders incite them to take revenge. Shouts of "Death to the Czar and to the Monarchy."

Horrendous tragedy. The tragedy acquired horrendous proportion in the middle of the afternoon. Troops keep shooting at workers. There are many dead.

Footnote. It is confirmed that Pope Gapon was wounded. He was holding a portrait of the Czar with his hands when he got hit.

The cossacks. In cavalry charges the horses of the cossacks trampled on the wounded.

Barricades. Barricades went up in one of St. Petersburg's neighbourhoods. The resistance is unbelievable. Troops wound or kill hundreds of strikers. All social classes rush to pick up the corpses lying on the streets.

Horrible butchery. Defenceless workers. A wish. A horrible butchery took place beside the Putilov Works. Workers lay flat on the ground, arms spread out to show they were unarmed, shouting that they only wished to see the Czar. The cossacks replied with their whips first and shot them afterward with a pendular swing of their rifles to make sure their victims perished.

Dynamite in action. Strikers took over a dynamite factory.

Official reports. The number of dead. Official reports put the number of dead at more than 2,000, Many women are part of the tally. The city offers a horrible aspect.

6. THE BEGINNING OF THE REVOLUTION IN RUSSIA.

Only an armed populace can be the real bulwark of popular liberty.

7. A LETTER TO A. A. BOGDANOV AND S. I. GUSEV.

Really, I sometimes think that nine-tenths of Bolsheviks are actually formalists. Either we shall rally all who are out to fight into a truly iron-strong organization and with this small but strong party quash that sprawling monster, the new-Iskra motley elements, or we shall prove by our conduct that we deserve to go under for being contemptible formalists.

How is it that people do not understand that prior to the Bureau of Committees of the Majority 1 and prior to "Vperyod" we did all we could to save loyalty, to save unity, to save the formal, i.e., the higher methods of settling the conflict?! But now, after the Bureau, after "Vperyod", the split is a fact. And when the split became a fact it was evident that we were very much weaker materially.

We have yet to convert our moral strength into material strength. The Mensheviks have more money, more literature, more means of transportation, more agents, more "names" and a larger staff of contributors. It would be unpardonable childishness not to see that. And if we do not wish to present to the world the repulsive spectacle of a dried-up, anemic old maid proud of her barren moral purity, then we must understand that we need war and a battle organization. Only after a long battle and only with the aid of an excellent organization can we turn our moral strength into material strength.

We need funds. The plan to hold the Congress in London is sublimely ridiculous for it would cost twice as much.2 We cannot suspend publication of Vperyod, which is what a long absence would mean. The Congress must be a simple affair, brief and small in attendance. This is a congress for organizing the battle. Clearly you are cherishing illusions in this respect.3

We need people to work on Vperyod. There are not enough of us. If we do not get two or three extra people from Russia as permanent contributors, there is no sense continuing to prate about a struggle against Iskra. Pamphlets and leaflets are needed and needed desperately.

We need young forces. I am for shooting on the spot anyone who presumes to say that there are no people to be had. The people of Russia are legion; all we have to do is recruit young people more widely and boldly, more boldly and widely, and again more widely and again more boldly, without fearing them. This is a time of war. The youth—the students, and still more so the young workers—will decide the issue of the whole struggle. Get rid of all the old habits of immobility, of respect for rank and so on.

8. A MILITANT AGREEMENT FOR THE UPRISING.

We take pleasure in publishing the following letter from Georgi Gapon,

An Open Letter to the Socialist Parties of Russia.

The bloody January days in St. Petersburg and in the rest of Russia have brought the oppressed working class face to face with the autocratic regime headed by the bloodthirsty tsar. The great Russian revolution has begun. All to whom the people's freedom is really dear must either win or die.

Realizing the importance of the present historical moment, considering the present state of affairs, and being above all a revolutionary and a man of action, I call upon all socialist parties of Russia to enter immediately into agreement among themselves and to proceed to an armed uprising against tsarism. All the forces of every party should be mobilized. All should have one specific action plan: bombs, dynamite, individual and mass terror—everything that can help the popular uprising.

The immediate aim is the overthrow of the autocracy, a provisional revolutionary government which will at once amnesty all fighters for political and religious liberties, at once arm the people and at once convoke a Constituent Assembly on the basis of universal, equal and secret ballot.

To the task, comrades! To the fight! Let us repeat the slogan of the St. Petersburg workers on the Ninth of January, "Freedom or Death!" Delay and disorder now are a crime against the people whose interests you are defending.

Having given my all to serve the people whence I come (son of a peasant) and having irrevocably thrown my lot in with the struggle against the oppressors and exploiters of the working class, I shall naturally be heart and soul with those who undertake the actual business of liberating the proletariat and all the toiling masses from the capitalist yoke and political slavery.

Georgi Gapon

On our part we consider it necessary to state our view of this letter as clearly and precisely as possible. We deem the proposed "agreement" possible, useful and essential. We welcome the fact that Gapon says "agreement" explicitly, since only through the preservation of full independence by each political party, on points of principle and organization, can a fighting unity be achieved; but we must be very careful not to spoil things by vainly trying to lump together heterogeneous elements. We shall inevitably have to march separately but we can strike together more than once and particularly now.

It would be desirable from our point of view to have this agreement embrace socialist and revolutionary parties even though the immediate goal of the struggle is not socialist at all;—we must not confuse or ever allow anyone to confuse our immediate democratic goals with our ultimate objective of a socialist revolution.

It would be desirable, and from our point of view essential, that instead of a general call for "individual and mass terror" the agreement should state openly and clearly that our joint action must actually fuse terrorism with the uprising of the masses. True, by adding the words, "everything that can help the popular uprising," Gapon clearly indicates his desire to make even individual terror subservient to this aim; but this desire ... should be expressed bluntly and absolutely guide all practical decisions unequivocally.

We should finally like to point out, regardless of the feasibility of the proposed agreement, that Gapon's extra-party stand seems to us to be another negative factor. Obviously Gapon was not immediately able to evolve for himself a clear revolutionary outlook, given his rapid conversion from faith in and petitioning the tsar to revolutionary action. This is inevitable, and the faster and broader the revolution develops, the more often will this kind of thing occur. Nevertheless complete clarity and rigor in the relations between parties, trends, and shades are absolutely necessary if a temporary agreement is to be reached.

9. SPEECH ON AN AGREEMENT WITH THE SOCIALIST-REVOLUTIONARIES.

I have to inform Congress about an unsuccessful attempt to come to an agreement with the Socialist-Revolutionaries.

Comrade Gapon arrived abroad. He met with the Socialist-Revolutionaries, then with Iskra people and finally with me. He told me that he shared the Social-Democrats' point of view but for various reasons did not deem it possible to say so openly. I told him that diplomacy was a good thing, but not between revolutionaries ... He impressed me as an enterprising and clever man, unquestionably devoted to the revolution, but unfortunately without a consistent revolutionary outlook.

Some time later I received a written invitation from Comrade Gapon to attend a conference of socialist organizations convened after his idea for the purpose of coordinating their activities. Here is a list of the eighteen organizations invited, according to that letter, to Comrade Gapon’s conference:

I pointed out both to Comrade Gapon and to a prominent Socialist-Revolutionary that the dubious make-up of the conference might create difficulties. The Socialist-Revolutionaries were building up an overwhelming conference majority. The convocation of the conference was greatly delayed. Iskra replied, as documents submitted to me by Comrade Gapon show, that it preferred direct agreements with organized parties. A "gentle" hint at Vperyod being an alleged disrupter, etc. In the end Iskra did not attend the conference. We, the representatives of both the Vperyod Editorial Board and the Bureau of Committees of the Majority, did attend. Arriving on the scene we saw that the conference was a Socialist-Revolutionary affair.

[...]

The question that led to our withdrawal concerned the Letts. On leaving the conference we submitted the following declaration:

The important historical period through which Russia is passing confronts the Social-Democratic and revolutionary-democratic parties and organizations working within the country with the task of reaching a practical agreement for a more effective attack on the autocratic regime.

While attaching very great importance to the conference, therefore, we must naturally subject the composition of the conference to the closest scrutiny.

In the conference called by Comrade Gapon the closest scrutiny has unfortunately not been observed and we were therefore obliged from the start to take measures calculated to ensure the genuine success of the gathering.

The fact that the conference was to deal solely with practical matters made it necessary, in the first place, to make sure that only organizations truly constituting a real force in Russia should participate.

Actually the conference's composition is most unsatisfactory as far as the authenticity of some organizations is concerned. Even an organization whose bogus nature is beyond doubt found representation. We refer to the Lettish Social-Democratic League.1

The Lettish Social-Democratic Labour Party representative objected to the seating of this League and couched his objection in the form of an ultimatum.

The utter fiction of the "League", subsequently confirmed at a special meeting of representatives from the four Social-Democratic associations and "League" delegates, naturally compelled us (Social-Democratic associations and parties present at the conference) to endorse the ultimatum.

However we met strong resistance from all the revolutionary-democratic parties which, by rejecting our peremptory demand, showed they preferred a counterfeit group to a number of well-known Social-Democratic organizations.

Finally the practical significance of the conference was further devalued by the absence of other Social-Democratic groups whose participation was obviated, as far as we could ascertain, through the carelessness of the conference organizers.

Though compelled to leave the conference in view of all this, we express our conviction that this one failure will not deter earnest efforts to renew the attempt in a very near future, and that the task of reaching a practical agreement among revolutionary parties will be accomplished by an upcoming conference of associations genuinely working in Russia.2,3

A week and a half or two weeks later Comrade Gapon sent me the following statement:

Dear Comrade,

I am forwarding two declarations issued by the conference you know of. I request that you publicize them at the forthcoming Third Congress of the R.S.D.L.P.

For my own part I accept the declarations with certain reservations concerning the socialist programme and the principle of federalism.

Georgi Gapon

10. POPE GAPON (Part I).

St. Petersburg: Gapon wrote the Czar asking him to accept the workers' petition. He also wrote the Minister of the Interior asking for his collaboration.

Gapon's letter to the Czar read,

Do not assume that ministers tell you the whole truth about the people's welfare ... The entire people places their trust in you ... If you do not meet them tomorrow out of fear, when they show up at the Winter Palace to expose their needs to you, you will have broken the moral bond that exists between you and them. Their trust will fade away and the blood of innocents will run.

The Metropolitan Council has dictated an anathema against Pope Gapon for having incited the people to revolution at such a difficult time for the country.

St. Petersburg: New reports. Gapon was momentarily detained on January 22 until 12:30 PM.

St. Petersburg: Pope Gapon received a bullet in the chest and is in "Alafoxi" Hospital. His condition has worsened considerably.

According to foreign newspapers, Gapon the son of a Moscovite mujik (peasant) distinguished himself for displaying a rebellious attitude toward the hamlet's elders.

Gapon wanted to become a worker but his father forced him to attend Moscow's Seminary. There he sided with the black clerics (low rank, poor) versus the white (high). He was influenced by Tolstoy whose excommunication he opposed.

After the Russian government legalized workingman societies Gapon organized a circle of mechanics and metal workers and attained great influence.

Though a faithful practitioner of Greek/Russian Orthodoxy he tolerates other religious beliefs and has Roman Catholics, Protestants, Jews, rationalists, etc., among his friends.

He is very frugal, devotes many hours a day to work and owns all the qualities of a revolutionary mystic. On occasion he appears to be an illuminato. His speech is concise, clear, lively and replete with quotations.

Though a disciple he does not embrace Tolstoy's passive attitude to evil. Rather he embodies the spirit of protest, action, struggle.

The government tried to lock his workers' club but refrained because its members produced matériel for the Russo-Japanese War.

Gapon is a declared enemy of gambling, alcoholism and other vices that coarsen the Russian populace; he lashes out violently against those who indulge in them.

The St. Petersburg Workers' Unions organ brands Gapon an agent provocateur. The newspaper adds that Gapon received 30,000 rubles from the government, spent only 7,000 and fled to Nice with the remainder.

London: A Russian revolutionary group claims that Gapon was hanged by the secret police.

St. Petersburg: A newspaper received a communiqué from a revolutionary tribunal stating that Gapon was executed for treason.

Paris: A newspaper correspondent claims that Gapon was arrested, punished severely and secluded in a convent for the rest of his life.

The autopsy of Gapon's corpse and collateral police investigations conclude that Gapon was lured into an ambush by the revolutionaries. They beat him furiously and when he was half-dead finished him off by strangling.

Gapon rented a safety deposit box in a branch of Le Credit Lyonais using the alias Rebisky. When the box was opened under judicial supervision it was found to contain two envelopes: one had 14,500 rubles in bills, the other fourteen 1,000-franc bills.

Gapon was buried on May 23. Friends and supporters attended his burial.

11. POPE GAPON (Part II).

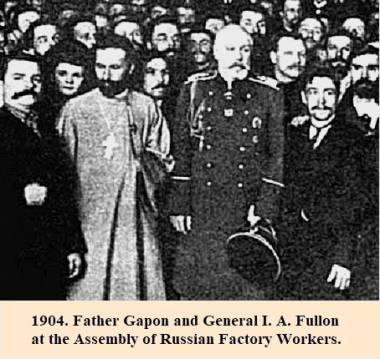

We called our society (avoiding that word lest it should excite suspicion) the Gathering (Sobranye) of Russian Factory Hands of St. Petersburg. Its stated aims were to strengthen national self-consciousness in the Russian worker, to hone his intelligence and capacity for self-help. As a means to these ends it would organize tea clubs, educational circles, lectures on industrial and general-interest subjects and co-operatives for production and distribution; sickness, accident and unemployment benefit societies would follow as soon as possible (pp. 111-12).

On April 11, 1904, the opening ceremony of the St. Petersburg Factory Workers' Society was held. About 150 people participated and after various speeches by the workingmen and myself there was music and dancing (pp. 117-18).

Mr. de Plehve the Minister of the Interior was assassinated on July 28, 1904, by the Socialist-Revolutionaries (p. 128).

I arranged a grand meeting on August 19, 1904, at the Pavlov Hall, one of the most prestigious in St. Petersburg. Crowds of workmen with their wives and children came, two thousand in all ... General Fullon visited us again, making his way to the platform through a corridor of cheering workmen (pp. 129-30).

I tried to get in touch with the Social Democrats and with the Revolutionary Socialists so that we could all work together if need arose, but they held aloof, still being suspicious of my organization on account of Fullon's favourable disposition to it (p. 134).

At the end of December 1904 four workmen at the Putilov Works were fired for being members of our society. Two had worked a score of years and the others about seven (p. 142).

On January 1, 1905 (Old Style December 19) I summoned a meeting on the matter. The revolutionary parties were invited and this was the first time they came (p. 143).

It was at this juncture (the official threat of a solidarity strike on January 3, 1905) that news of Port Arthur's surrender arrived. It triggered great indignation and propelled the people to stick with the movement. I asked some of the more influential Putilov workers whether they could stop the entire works; they replied "yes" emphatically (p. 149).

I now invited the leaders of the revolutionary parties to join us in supporting the strike. Our members greeted them with some animosity at first, but I wielded my influence and a bond was made (p. 159).

On the evening of January 21 (Old Style January 8) in a room adjoining one of our branch halls I found several representatives of the Socialist-Revolutionary and Social-Democratic parties. Though exhausted, I could not refuse to discuss our plans over with them. "We shall go on Sunday as we have planned," I said. "Do not show any flag of yours so the demonstration will not seem revolutionary. You may go ahead of the crowd if you like. When I enter the Winter Palace I will carry two flags, one white and one red. If the Tsar receives the deputation I will signal with the white flag; if he refuses I will signal with the red flag and in that case you may raise your own red flag and do whatever you esteem necessary" (p. 170).

Cognizant of reports about a massive military deployment the idea came to me that it would be good to give the procession a distinctly religious character. Accordingly I dispatched some men to the nearest chapel to get church banners and icons; but the sexton refused to give them up. I then sent a hundred workmen to take them by force and a few minutes later they brought the items. I also ordered that the Tsar's portrait hanging in our branch halls should also be carried aloft to emphasize the peaceful and orderly nature of our march. The crowd had now grown to immense proportions. Men came with their wives, some with their children, all dressed in their Sunday best; and I noticed that arguments or disputes among them were halted with the instruction, "This is not the time for talking" (p. 178).

Again we started at the Narva Gate, and again the firing began.1 After the last volley I rose again and found myself alone but still unhurt. Suddenly, in the midst of my despair, somebody took hold of my arm and dragged me quickly away into a small side street a few paces from the scene of the massacre. It was idle for me to protest. What more could be done? "There is no longer any Tsar for us!" I exclaimed (p. 185).

In the by-street we were approached immediately by three or four of my workmen, and I recognized in my rescuer the engineer who had seen me the previous night at the Narvskaya Zastava. He took out a pair of scissors from his pocket and cut off my priestly locks, these the men immediately parcelled out among themselves. One rapidly tore off my cassock and hat and gave me his overcoat, but it seemed to be smeared with blood. Then another poor fellow took off his ragged coat and cap and insisted on my wearing them. It was all done in two or three minutes. The engineer urged me to go with him to the house of a friend, and I decided to do so (p. 186).

I learned in the next few hours that the other branches of our association had suffered a similar fate. Aside from the small branches whose headquarters were downtown the main starting points for the various marches were: (1) the city's south-west (ours); (2) Peterburgskaya Storona beyond the Little Neva, on the north; (3) Basil Island (Vassily Ostroff) between the Great and Little Neva; and (4) Schlusselburg Road beyond the Neva, on the south-east.2

At the Peterburgskaya District branch a great crowd gathered in the morning, awaiting the start of the procession. It displayed the most peaceful spirit, no violence expected, and several mounted soldiers passing by stopped to ask our men for matches to light their cigarettes and share a friendly word with them. Before the march got underway the news arrived that troops barred the way to the Palace and that men and women had already been struck down by sword-wielding Cossacks. Nevertheless the procession set out toward Troitsky Bridge and converged with another throng coming from the Viborgskaya District (somewhat to the north-east) and their headquarters on Orenburgskaya Street. The joint procession was unmolested for a long stretch until it drew near Alexandrovsky Park behind the Peter and Paul Fortress. There they met infantry companies barring the way to Troitsky Bridge (pp. 188-89).

At last we reached our destination. It was now about 1:00 PM. The lady of the house shut me up in a room and gave me some food, which, to my astonishment, I devoured with appetite. Then I was handed a student's apparel and moved to another house where I changed once more into an ordinary suit and had my beard shaved off. After that I was taken to the home of the famous Russian writer X.3 He was greatly excited at seeing me and, embracing me, began to cry. He gave me a glass of red wine and pressed me to stay with him, but suddenly the torturing thought overwhelmed me that people were dying outside at this very moment and that I must go to die also. X stopped me and convinced me that it would be better to go with him to a meeting of "intellectuals" a little later in the day, to be followed by a secret one which would vet the chances of procuring weapons for the people (p. 206).

On Monday January 23 I sent some members of the revolutionary party I was acquainted with to find the more prominent workmen who had led the various processions. Not one could be located. Some had been killed or wounded and others avoided their homes for fear of arrest. During that day and Monday night the shooting of men and women continued about the capital albeit on a smaller scale. According to my calculations, between six hundred to nine hundred people were slain on the fateful Sunday and at least five thousand were wounded. The whole town resembled a besieged city. All shops, restaurants and theatres were closed. The Tsar and his family were still in hiding; nobody knew where (p. 211).

During the two days following Bloody Sunday I changed my address several times for the authorities were combing the city, eager to catch me (pp. 218-19).

On the evening of January 24 General Trepov was installed at the Winter Palace and made Dictator of St. Petersburg. He always looked on me most unfavourably, as I have said, and I knew him to be a despot of the most cruel and unswerving ilk (p. 220).

That very night all members of a Liberal deputation which at my request went to see Prince Sviatopolk-Mirski and Mr. Witte were arrested and thrown in the Peter and Paul Fortress. The deputation was composed of Maxim Gorky, barrister Hessen, famous historian Karayev, political writer Peshekonov, Professor Myakotin, Semevsky the historian, Kedrin the city councillor, Pissarev the editor of Russian Wealth and barrister Sitnikov. At the same time wholesale arrests began all over the capital and I learned that all my best workmen who had had the good fortune of escaping death had been jailed (pp. 220-21).

But where could I escape to? Some of my new friends suggested a certain location in Finland, others different places in the countryside near St. Petersburg. Messengers informed us that spies roved everywhere, passports were checked rigorously and the police were looking for me on all sides. At last we picked a hideout and worked out the necessary details. The Liberal barrister who had helped me so devotedly gave me his own passport. I promised to return it as soon as I reached safety (pp. 221-22).

I must explain that all along the western frontier of Russia a considerable segment of the population makes a living working as professional smugglers of people or goods, striking deals with the border guards on duty. A guard usually gets 1-3 rubles per migrant he lets across (p. 239).

On my arrival to Tilsit 4 I obtained my first opportunity to get a shave, after which, my driver dropped me off at the home of a young man recommended by my St. Petersburg friends. I found heaps of Russian revolutionary publications in every room of the house. My curiosity was kindled, but my host did not speak a word of Russian! which is the only language I speak. At last he brought a friend who knew Russian, a very sympathetic fellow, N----; and I soon understood that the house was a hotbed of revolutionary activity. People came and went, packing and taking away parcels of clandestine literature. I wondered how much my host knew about me and what his opinion of the recent events was, so I steered our conversation thereto. He showed utmost interest and spoke about Father Gapon with great sympathy. I decided to trust him and on a pledge of confidentiality told him who I was. He was quite startled and questioned me to check me out. At last he was convinced and said that he and N---- were members of the Lettish Social Democratic League (p. 245).5

12. DEBACLE.

The Russian warships flung themselves like a horde of savages headlong upon a Japanese fleet magnificently armed and equipped with the most up-to-date means of defence. Thirteen of Russia's twenty warships manned by from twelve to fifteen thousand sailors were sunk or destroyed after a two-day battle, four were captured and only one (the Almaz) escaped and reached Vladivostok. More than half the crews were killed or drowned and Rozhdestvensky "himself" and Nebogatov his right-hand man were taken prisoner. The Japanese fleet lost three destroyers.

Russia's naval strength has been completely destroyed. The war has been irretrievably lost. The complete expulsion of Russian troops from Manchuria and the seizure of Sakhalin and Vladivostok by the Japanese are only a matter of time. We are witnessing not just a military defeat but the complete military collapse of the autocracy.

13. THE REVOLUTIONARY ARMY AND THE REVOLUTIONARY GOVERNMENT.

The uprising of Odessa and the siding of the armoured cruiser Potemkin with it marked another big step forward in the march of the revolutionary movement against the autocracy.

14. KNIAZ POTEMKIN.

The crew aboard a battleship moored at Odessa has mutinied, killing the Commander and the officers. The crew had been complaining for a long time about the rotten food they were served. The sailors sent a spokesman to lodge a complaint with the Commander, who shot him. The Commander's action triggered the mutiny. The rebel vessel then signalled Odessa to deliver food and ammunition or the city would be shelled. The revolutionists set fire to the port's installations.

London: Crews of another four battleships in Sevastopol have mutinied and are sailing to Odessa. The Odessa uprising provoked 1,000 deaths and 3,000 wounded on the night of June 28. Troops fired with machine-guns. Three officers, ten Cossacks, eight policemen and twenty-three soldiers perished. A Potemkin tender landed the corpse of the murdered spokesman. Many stevedores fraternized aboard the battleship with the mutineers. The government shut the port's warehouses down.

St. Petersburg: Odessa merchant-fleet crews fraternized with the Potemkin mutineers. The battleship's magazine stores 3,000 rifles and many machine-guns. The crew is 930 sailors. People are fleeing the city.

Odessa: The rebel battleship is the Kniaz Potemkin the flagship of the Black Sea Fleet. It arrived to Odessa from Sevastopol accompanied by a torpedo boat which the mutineers used to co-opt 2,000 tonnes of coal from a Russian steamboat in the harbour. The blaze has spread from the harbour to the cathedral.

St. Petersburg: Admiral "Tchikin" (?) was dispatched to Sevastopol with the mission of destroying the Potemkin. The Odessa harbour fire is formidable; many buildings, several steamships and boats are alight.

The burial rite with honours for the murdered spokesman took place yesterday afternoon in an atmosphere of great solemnity. The numerous public in attendance included popes who blessed the ceremony. Gunfights between civilians and troops have provoked 2,000 dead and 4,600 wounded. The troops were ordered to obliterate the harborside neighbourhoods where barricades went up.

St. Petersburg: Krondstat's sailors have also mutinied. The Kniaz Potemkin Tavritchski is shelling Odessa, causing extensive damage.

St. Petersburg: A general strike has been called. Some reports affirm that Potemkin has surrendered or been sunk by the Black Sea Fleet. Other reports deny it. Several European nations will send warships to Odessa to protect their nationals.

Strict press censorship obscures the truth of what is happening in Odessa.

St. Petersburg: Odessa has been occupied by 30,000 soldiers.

London: Battleship Potemkin did not surrender but left Odessa for Constanza (Romania). Another report affirms that Potemkin is still in Odessa, threatening to bombard the city.

Sevastopol: The Black Sea Fleet obstinately refuses to open fire on Potemkin.

London: Telegrams evince that Russia is in a state of complete anarchy.

St. Petersburg: The battleship that threatened to shell Odessa if the city did not surrender within twenty-four hours was not Potemkin but the Georgii Pobedonosets.

St. Petersburg: The crew of Kniaz Potemkin has convinced the crew of the cruiser "Ochadff Constanne" (?) to join them. The gunboat "Ressumpe" (?) has also enrolled. Mutineer commissions acquired a large cargo of food and coal in Constanza (Romania); local authorities pressed them to depart as soon as possible.

Constanza: The mutineers refuse to set sail; the authorities threaten to sink Potemkin if it does not leave. Russian cruiser Minin has joined the rebellion.

Constanza: Potemkin had only ten tonnes of coal left and enough food for two days. A section of the crew wants to surrender, others propose blowing up the warship. Many sailors sought sanctuary on a British cruiser. Potemkin arrived in Theodosia (Crimea) petitioning food and threatening to shell the city if the petition was rejected.

St. Petersburg: Strikes spread. Confrontations between workers and soldiers caused many dead and wounded at Putilov Works.

Tiflis: The call for a general strike was seconded by a very considerable number of workers.

Odessa: Calm has been restored. The total count of dead rises to 5,000 and the number of wounded to 8,000. Potemkin threatened a German colony with bombardment unless the Germans handed over their cattle.

Sevastopol: The Black Sea Fleet returned to port carrying the actors of the Georgii Pobedonosets rebellion.

Kronstadt: Three thousand soldiers and sailors threaten to join the revolutionary tide.

Tiflis: Gunfights between striking workers and policemen.

Akkerman: Potemkin arrived accompanied by a torpedo boat, and requested food.

Theodosia: Its harbour batteries opened fire on Potemkin; the battleship responded.

St. Petersburg: The Army presented the Czar with an ultimatum to implement the reforms desired by the country.

Bucharest: The director of the port (Constanza) assumed control of Potemkin and raised the Romanian flag on it despite the protests of the crew.

The Romanian government has informed the Czar he may recoup Potemkin at his discretion.

The Russian Navy has been ordered to retake possession of the vessel.

Constanza: Potemkin's crew landed, battleship and torpedo boat lie at anchor in the harbour. Another report says that torpedo boat number 267 opted to leave and head to Sevastopol.

London: A dispatch from Constanza states that seven Russian officers were discovered on board the Potemkin in a very pitiable state owing to ill treatment.

St. Petersburg: Potemkin's pal docked in Sevastopol. The whole crew is sick and under summary arrest.

St. Petersburg: The Romanian government will not lay claim to the ⅓ compensation slated for salvaging Potemkin. The Romanian government will not turn Potemkin's deserters in because, it says, these surrendered the battleship on the understanding that they would not be delivered to Russian authorities. The Romanian statement added that the mutineers will be treated like Macedonian refugees.

However fifty sailors turned themselves in to Russian authorities, alleging that they had participated in the revolutionary movement under duress.

Constanza: An officer was discovered in very poor shape inside a locked cabin of Potemkin. He had been restricted to a diet of bread and water from the outset of the mutiny. His condition is serious.

LAST HOUR: Potemkin is back in Sevastopol.

15. THE RUSSIAN TSAR SEEKS THE PROTECTION OF THE TURKISH SULTAN AGAINST HIS PEOPLE.1

Peasant uprisings have broken out in five uyezds of Kherson Gubernia.2 Nearly 700 peasants were killed in the last four days.

"A life-and-death struggle between the people and the bureaucracy has apparently started," says a telegram from Odessa to London dated New Style July 5.

| And Now For Something Completely Different |