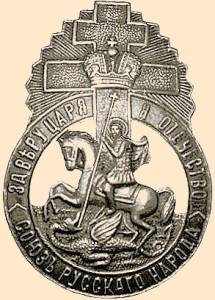

Black Hundreds parade in Odessa, 1905. Union of the Russian People badge.

Source: Russian Wikipedia

1. THE BOYCOTT OF THE BULYGIN DUMA, AND INSURRECTION.

At present the political situation in Russia is as follows: the Bulygin Duma 1 may soon be convened—a consultative assembly of representatives of the landlords and the big bourgeoisie, elected under the supervision and with the assistance of the autocratic government's servants on the basis of an electoral system so indirect, so blatantly based on property and social-estate qualifications, that it is sheer mockery of the idea of popular representation. What should our attitude towards this Duma be? The liberal democrats give two replies to this question. The Left wing, represented by the "Union of Unions"—mostly representatives of the bourgeois intelligentsia—is in favour of boycotting this Duma, of abstaining from participation in the elections, and of taking advantage of the opportunity for increased agitation for a democratic constitution on the basis of universal suffrage. The Right wing, as represented by the Zemstvo and Municipal Congress of July, or, to be more correct, by a certain section of that Congress, is opposed to a boycott and favours participation in the elections and getting as many of its candidates as possible elected to the Duma.

[...]

At present the Left wing of bourgeois democracy itself has raised the issue of waging a direct and immediate struggle against the Duma by means of a boycott, and we must exert all our efforts to support this more determined onslaught. We must take the bourgeois democrats, the Osvobozhdeniye people,2 at their word, give the widest publicity to their "Petrunkevich-like" 3 phrases about an appeal to the people, expose them to the people and show that the first and least real test of these phrases was the question of whether we should boycott the Duma ... or accept the Duma ...

Secondly we must exert every effort to make the boycott of real use in spreading and intensifying agitation so that it shall not be reduced to mere passive abstention from voting. If we are not mistaken this idea is already fairly widespread among the comrades working in Russia who express it in the words: an active boycott. As distinct from passive abstention, an active boycott should imply increasing agitation tenfold, organizing meetings everywhere, taking advantage of election meetings, even if we have to force our way into them, holding demonstrations, political strikes and so on and so forth.4

2. ONENESS OF THE TSAR AND THE PEOPLE, AND OF THE PEOPLE AND THE TSAR.

In Proletary, No. 12, which appeared on August 3 (16), we spoke of the possibility of the Bulygin Duma being convened in the near future, and analyzed the tactics of Social-Democracy towards it. The Bulygin scheme is now law and the Manifesto of August 6 (19) proclaims that a "State Duma" will be called "no later than mid-January 1906."

It is on the anniversary of January 9, when St. Petersburg workers placed the seal of their blood on the beginning of the revolution in Russia and showed their determination to fight desperately for its victory—it is on the anniversary of that great day that the tsar proposes to convene this grossly faked, police-sifted assembly of landowners, capitalists and a negligible number of rich peasants who cringe to the authorities. The tsar intends to consult this assembly as if it consisted of representatives of the "people"; but the entire working class, the millions of toilers and all those who are not householders are completely barred from electing the "people's representatives." We shall wait and see whether the tsar is right in banking on the impotence of the working class thus...

Until the revolutionary proletariat has armed itself and defeated the autocratic government nothing but this sop to the big bourgeoisie could have been expected, a sop that costs the tsar nothing and commits him to nothing.

Even this sop would probably not have been granted at this time if the ominous question of war or peace did not loom large. The autocratic government does not venture to impose on the people the burden of a senseless continuation of the war, nor devise measures that shift the entire financial burden of the war from the shoulders of the rich onto the shoulders of the workers and peasants, without first consulting the landlords and the capitalists.

As for the provisions of the State Duma Act, they fully confirm our worst expectations. It is not yet known whether this Duma will actually be convened. Such doles can easily be removed, autocratic monarchs in every country have made and broken similar promises by the score. It is not yet known to what extent this future Duma, if it meets at all and is not revoked, will be able to become the centre of political agitation against the autocracy reaching really far within the masses of the people. But there can be no doubt that the very provisions of the new State Duma Act furnish us with a wealth of material for agitation, to disclose the nature of the autocracy, to reveal its class basis, to explain the irreconcilability of its interests with the people's and to spread and popularize our revolutionary-democratic demands. It may be stated without exaggeration that the Manifesto and Act of August 6 (19) ought to be a vademecum for every political agitator, every class-conscious worker. They mirror exactly the infamy, viciousness, Asiatic barbarity, violence, and exploitation that pervade the whole social and political structure of Russia. Practically every sentence of Manifesto and Act provides excellent material for a most comprehensive and persuasive political commentary that will stimulate democratic thought and revolutionary consciousness.

As the Russian saying runs: "Leave it alone and it won't stink." When one reads the Manifesto and the State Duma Act one feels as though a pile of sewage amassed since time immemorial were being stirred underneath one's very nose.

3. THE BLACK HUNDREDS AND THE ORGANIZATION OF AN UPRISING.1

One cannot help being agitated by what is taking place in Russia at the present time; one cannot help thinking of war and of revolution, and whoever is agitated, whoever thinks, whoever takes an interest, is obliged to join one armed camp or the other. You may get beaten up, maimed or murdered no matter how supremely peaceful and scrupulously lawful you behave. Revolution does not recognize neutrals.

Black Hundred ideology exploded across Western Europe prior to the Second World War (Spain, Portugal, Italy, France, Great Britain). Fascist parties possessed a blinkered view of their country's past and, like the Russian Black Hundreds, wanted to recapture misconstrued years of splendour in light of an internal threat of social revolution. Germany's case is in a different category.

4. A NEW MENSHEVIK CONFERENCE.

Three resolutions were adopted at the Menshevik conference (May 1905, Geneva) on the composition of the Menshevik Iskra's Editorial Board, yet the question was not settled.1 One resolution asks Axelrod not to leave the Editorial Board; another requests Plekhanov to return to it (he had resigned); the third thanks Iskra, expresses complete confidence in it, etc., but refers the question to an "all-Russia constituent conference for a final decision."

5. DAYS OF BLOODSHED IN MOSCOW.

It began with a typesetters' strike that spread rapidly. On Saturday September 24 (October 7) the printing shops, electric trams and tobacco factories were already at a standstill. No newspapers appeared and a general strike of factory and railway workers was expected. In the evening big demonstrations of typesetters, other trades, students and so on. Cossacks and gendarmes dispersed the demonstrators time and again but they kept reassembling. Many policemen were injured; the demonstrators used stones and revolvers; a gendarme commander was severely injured. A Cossack officer and a gendarme were killed and so on.1

On Saturday the bakers joined the strike.

On Sunday September 25 (October 8) events at once took an ominous turn. From 11 A.M. workers began to assemble in the streets—especially on Strastnoi Boulevard and elsewhere. The crowd sang La Marseillaise. Printing shops that refused to go on strike were wrecked.2

6. THE OCTOBER STRIKE.

St. Petersburg: A train has derailed; twenty-two passengers dead, thirty-seven hurt.

Moscow: Students intervened in yesterday's riots; fifty Cossacks were hurt.

Tiflis: Nine bombs were hurled at a detachment of Cossacks; ten died.

Moscow: Four hundred workers looted the bakeries for bread. Troops were called in. The workers commandeered a house, attacked the soldiers from the rooftops and offered resistance for six hours. Several people were killed or wounded.

St. Petersburg: A regiment mutinied and slew a colonel and fourteen officers.

Moscow: A confrontation between people and troops yielded a hundred dead and five hundred wounded.

Manchuria: Part of the Russian troops stationed there have mutinied and demand to be given land in Moscow.

Tiflis: New lobbing of grenades; there are many dead and wounded.

Moscow: The troops wounded women and children in a cruel deportment.

Baku: Several confrontations between people and troops left a hundred and eighty-five dead, six hundred wounded.

Moscow: Savage confrontations between troops and workers. The situation is completely out of control.

St. Petersburg: Seven hundred workers assaulted a bicycle factory; four dead, twenty-seven wounded. The declaration of a state of war across the Empire seems inevitable.

Moscow: All railway employees went on strike. Barricades went up near Rozhdestvenskiy Blvd. Six Cossacks were seriously injured. The chief of police was shot dead as he returned home with his family.

Tokyo: The peace treaty between Japan and Russia signed on the 15th goes into effect on the 17th.

Moscow: Twenty thousand workers joined the strike.

Ekaterinoslav: The British manager of a factory was killed by a bomb.

Moscow: New riots.

Nebogatov: A grenade was hurled at a detachment of Cossacks.

Moscow: The All-Russian League of Railways has called a general strike in a bid to obtain political reforms for the country.

St. Petersburg: Witte is almost certain to be named the next Prime Minister.

Moscow: A confrontation between workers and troops yielded sixty dead and a hundred and twenty wounded.

St. Petersburg: The railway strike has spread significantly. Seventy trains fetching meat to the capital were halted. The workers issued an ultimatum to the government. Most railway traffic across the Empire is at a standstill. Witte has been appointed President of the Council of Ministers.

Kharkov: Twenty thousand workers gathered for a meeting; the Cossacks dispersed it. There were many wounded and multiple arrests.

Moscow: The situation remains critical.

St. Petersburg: Strikes are spreading everywhere. There were recurrent confrontations between strikers and policemen; many dead and a considerable number wounded as a result. Hundreds of passengers stranded by the railway strike are eating and sleeping inside the coaches. Food is becoming scarce. Troops guard public buildings. Widespread looting in the suburbs. Strikers sent an ultimatum to Witte demanding universal voting rights. University students convene meeetings where economic, social and political questions are discussed vigorously; several thousand people attend.

Kharkov: The revolutionists have proclaimed a provisional government.1

The number of strikers has reached one million. Warsaw and Lodz announce a general strike from tomorrow.

St. Petersburg: The revolution spreads. An artillery corps detachment guards the Czar's Palace.

Ekaterinoslav: High School students went on strike.

Sevastopol: People have set the battleship Kniaz Potemkin on fire.1,2Warsaw: A million revolvers were distributed among workers.

St. Petersburg: Rumour has it that the Czar will flee the capital shortly and that General Witte was given dictatorial powers. Other rumours say that the Czar will grant the desired reforms soon. The university has been shut down. The Duma called an extraordinary session.

Odessa: Three armories were looted. Troops opened fire and killed twenty-six looters, wounded seventy.

London: Several Russian battalions joined the uprising.

Sevastopol: Rumour has it that the majority of the sailors on Kniaz Potemkin drowned, the Navy Minister also perished.1

London: The uprising across the Russian Empire acquires alarming proportions.

St. Petersburg: The Czar is dithering between giving Grand Duke Alexei dictatorial powers or granting constitutional reforms. Even Trepov advises constitutional reform. Apparently the Czar has opted for constitutional reform and suspended martial law. The Czar will issue a Manifesto tomorrow. Foreign negotiators of a loan to Russia leave St. Petersburg in light of the serious situation. Foreign embassies and consulates were instructed to guarantee the lives of their nationals.

Warsaw: Strikes have spread alarmingly. Strikers scuttled many railway tracks and telegraph posts.

Odessa: Twenty-seven dead, two hundred and eighty-seven wounded. The general strike has provoked a shortage of food and coal.

St. Petersburg: The Czar sanctioned a Constitution that proclaims freedom of conscience, speech, meetings and association; new elections will take place and all citizens may vote. The Strike Committee has advised a general return to work. Great enthusiasm reigns. Intellectuals embrace one another in the streets, cafés and public places. Streets are festooned with flags, banderoles, garlands and streamers.

Moscow: Calm has returned.

Odessa: Calm has returned.

Paris: L'Echo de Paris insinuates that Germany has been financing the revolutionaries of Russia.

7. TO THE COMBAT COMMITTEE OF THE ST. PETERSBURG COMMITTEE.

It horrifies me—I give you my word—it horrifies me to find out that there has been talk about bombs for over six months 1 yet not one has been made! And it is the most learned people who are doing the talking... Go to the youth, gentlemen! That is the only remedy! Otherwise—I give you my word for it—you will be too late (everything tells me that) and will be left with "learned" memoranda, plans, charts, schemes and magnificent recipes but without an organization, without a living cause. Go to the youth.2 Form fighting squads at once everywhere, among students, and especially among workers, etc., etc. Let groups of three, ten, thirty, etc., persons be organized at once. Let them arm themselves at once as best they can, be it with a revolver, a knife, a rag soaked in kerosene for starting fires, etc.

[...]

Squads must begin military training at once by launching operations immediately, at once. Some may kill a spy or blow up a police station at once, others raid a bank to confiscate funds for the insurrection, others again may drill or prepare plans for localities, etc. But the essential thing is to begin at once to learn from actual experience: have no fear of these trial attacks. They may of course degenerate into extremes, but that is an evil of the morrow, whereas the evil today is our inertia, our doctrinaire spirit, our learned immobility and our senile fear of initiative. Let every group learn if it is only by beating up policemen: a score or so victims will be more than compensated for by the fact that this will train hundreds of experienced fighters who will be leading hundreds of thousands tomorrow.

8. THE AGGRAVATION OF THE SITUATION IN RUSSIA.

It is under this headline that the Berlin liberal Vossische Zeitung has published the following interesting dispatch:

It is with irresistible force that events are moving in the empire of the tsars. It must be obvious to every impartial observer that neither the government nor the opposition or revolutionary parties controls the situation. The late Prince Trubetskoi and other professors of higher educational institutions made vain attempts to dissuade students from the dangerous path they took when they decided to convert universities into places of political mass meetings. The students paid enthusiastic homage to the memory of Trubetskoi, marched massively in the funeral procession and turned the obsequies into an imposing political demonstration, but they did not follow his advice to keep outsiders out of the University. Mammoth meetings that last from early morning until late at night are being held at the University of St. Petersburg, at the Mining Academy and at the Polytechnical. Students are often in the minority. Impassioned and fiery orations are delivered, revolutionary songs sung. Moreover the liberals are roundly berated at these meetings for their half-heartedness especially, no accidental attribute of Russian liberalism, it is claimed, but a quality conditioned by eternal historical laws.

Not even General Trepov has faith in his own cause. He does not conceal from his friends that he considers himself a doomed man and that he expects no favourable results whatever from his administration. "I am merely fulfilling my duty and shall fulfil it to the end," he says.

The tsar's throne must be in a sad way indeed if the head of the police arrives at such conclusions. And indeed it cannot but be recognized that despite all of Trepov's efforts, despite the feverish activity of endless commissions and conferences, the tension has not only failed to relax since last year but has even become much more acute. The situation has grown worse and more ominous wherever one looks, everywhere the situation has worsened noticeably.

[...]

We shall bend all our efforts to bring this victory of workers and peasants to its consummation, to bring about the utter destruction of all the loathsome institutions of autocracy, monarchy, bureaucracy, militarism and serf-ownership. Only such a victory will put a real weapon into the hands of the proletariat—and then we shall set Europe ablaze, to make the Russian democratic revolution the prologue of an European socialist revolution.

9. THE ALL-RUSSIA POLITICAL STRIKE.

The foreign bourgeois press, including even the most liberal newspapers, is horrified by the "terrorist and seditious" slogans proclaimed by speakers at the free popular meetings, as though the tsar's government had not itself, through its policy of oppression, made insurrection imperative and inevitable.

10. TASKS OF REVOLUTIONARY ARMY CONTINGENTS.

The fight against the Black Hundreds is an excellent type of military exercise that will train soldiers of the Revolutionary Army, give them their baptism of fire and be at the same time of tremendous benefit to the revolution. Revolutionary Army groups must at once find out who organizes the Black Hundreds, where and how they are organized, and then, without confining themselves to propaganda, useful but inadequate, they must act with armed force, beat up and kill members of the Black-Hundred gangs, blow up their headquarters, etc., etc.1

11. A SOCIAL-DEMOCRATIC SWEETHEART.

To acclamation from Osvobozhdeniye Comrade Starover 1 continues to repent in the new Iskra for the sins he committed (unwisely) in the old Iskra.

Comrade Starover very much resembles the heroine of a story by Chekhov entitled, Sweetheart. At first Sweetheart lived with an impresario and used to say, "Vanichka and I are staging serious plays." Later she lived with a timber merchant and would say, "Vasichka and I are indignant at the high duties on timber." Finally she lived with a veterinary surgeon and used to say, "Kolechka and I doctor horses."

It is the same with Comrade Starover. "Lenin and I" abused Martynov. "Martynov and I" are abusing Lenin.2 Charming Social-Democratic Sweetheart! In whose embrace will you find yourself tomorrow?

12. THE FIRST VICTORY OF THE REVOLUTION.

Late Monday night the telegraph brought Europe news of the tsar's Manifesto of Old Style October 17th. The Times correspondent wired: "The people have won the day. The Emperor has surrendered. The autocracy has ceased to exist." Friends of the Russian revolution living in distant Baltimore (U.S.A.) expressed themselves differently in a cable they sent to Proletary: "Congratulations on the first great victory of the Russian revolution."

[...]

October 17th will go down in history as one of the great days of the Russian revolution. On this day the nation-wide strike, the likes of which the world had never seen before, reached its climax. The mighty arm of the proletariat, raised in an outburst of heroic solidarity all over Russia, brought the entire industrial, commercial and administrative life of the country to a standstill. It was the lull before the storm. Reports, one more alarming than the other, began pouring in from various big cities. The troops wavered. The government refrained from taking repressive measures. The revolutionaries had not yet launched any serious open attacks but insurrection was breaking out on all sides.

| And Now For Something Completely Different |