1908. St. Petersburg clinic vaccinating against cholera

Sources: webpage and Lunapic

1. ON THE "NATURE" OF THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION.

The experience of the two Dumas handed liberalism a complete fiasco. It did not succeed in "taming the muzhik"; it did not succeed in making him modest, tractable, ready for compromise with the landlord autocracy. The liberalism of the bourgeois lawyers, professors and other intellectualist trash could not "adjust itself" to the "Trudovik" peasantry and liberalism revealed itself to lag politically and economically far behind the peasantry. And the whole historic significance of the first period of the Russian Revolution may be summed up thus: liberalism has already demonstrated its counter-revolutionary nature conclusively, its incapacity to lead the peasant revolution; but the peasantry has not yet fully understood that it is only along the path of revolution and republic, under the guidance of the socialist proletariat, that a real victory can be won.

[...]

Even the clergy—those ultra-reactionaries, those Black-Hundred obscurantists purposely maintained by the government—have gone farther than the Cadets in their Agrarian Bill. Even they have begun talking about lowering the "artificially inflated prices" of land and about a progressive land tax that would exempt those holdings below the subsistence standard.

Why has the village priest—that policeman of official orthodoxy—proven to be more on the side of the peasant than the bourgeois liberal? Because the village priest has to live side by side with the peasant, to depend on him in a thousand different ways, and sometimes—as when priests do small-scale agriculture on church land—even be in a peasant's skin himself. The village priest will have to return from the most police-ridden Duma to his own village: and however much the village has been purged by Stolypin's punitive expeditions or chronic billeting of the soldiery, there is no return to it for those who have taken the side of the landlords. So it turns out that the most reactionary priest finds it more difficult to betray the peasant to the landlord than the enlightened lawyer and professor.

Yes, indeed! Drive Nature out the door and she gets in through the window. The nature of the great bourgeois revolution in peasant Russia is such that only the victory of a peasant uprising, unthinkable without the proletariat as guide, is capable of bringing that revolution to victory in the teeth of the congenital counter-revolutionism of the bourgeois liberals.

2. LEO TOLSTOY 1 AS THE MIRROR OF THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION.

To identify the great artist with the revolution which he has obviously failed to understand, and from which he obviously stands aloof, may at first sight seem strange and artificial. A mirror that reflects badly could hardly be called a mirror. Our revolution, however, is extremely complex. Among the mass of those who are directly making and participating in it there are obviously many social elements that have also not understood what is taking place and that also stand aloof from the real historical tasks the course of events has confronted them with. And if we have a really great artist before us he must have reflected at least some essential aspects of the revolution in his work.

[...]

The contradictions in Tolstoy's works, views, doctrines, in his school, are indeed glaring. On the one hand we have the great artist, the genius who has not only drawn incomparable pictures of Russian life but has made first-class contributions to world literature. On the other hand we have the landlord obsessed with Christ. On the one hand the remarkably powerful, forthright and sincere protest against social falsehood and hypocrisy, and on the other the "Tolstoyan", i.e., the jaded hysterical sniveller called the Russian intellectual who publicly beats his breast and wails: "I am a bad wicked man but I am practising moral self-improvement: I don't eat meat any more, I eat rice cutlets now." On the one hand merciless criticism of capitalist exploitation, exposure of government outrages, the farcical courts, the state administration, the unmasking of the profound contradictions between the growth of wealth, the achievements of civilization and the growth of poverty, degradation and misery among the working masses. On the other, the crackpot preaching of submission, "resist not evil" with violence. On the one hand the most sober realism, the tearing away of all and sundry masks; on the other the preaching of one of the most odious things on earth, namely religion, the striving to replace officially appointed priests by priests who will serve out of moral conviction, i.e. to cultivate the most refined and therefore particularly disgusting clericalism.2

[...]

Tolstoy reflected the pent-up hatred, the ripened striving for a better lot, the desire to get rid of the past, but also immature dreaming, political inexperience, revolutionary flabbiness. Historical and economic conditions explain the inevitability of the masses' revolutionary struggle and concurrently their unpreparedness for it, their Tolstoyan non-resistance to evil, a most serious reason for the defeat in the first revolutionary campaign.

Capitalism keeps evolving by the hour and intensifying those conditions which roused millions of peasants to the revolutionary-democratic struggle bonded by common hatred of feudalist landlords and government. The growth of commerce, the laws of the market and the power of money are steadily eroding the old-fashioned patriarchalism among the peasantry, and the patriarchal Tolstoyan ideology. But from the first years of the revolution and from the first reverses in mass revolutionary struggle there emerges one gain about which there can be no doubt. It is the mortal blow struck at the former softness and flabbiness of the masses. The lines of demarcation have become sharper. The cleavage of classes and parties is a fait accompli. Beneath the hammer blows of Stolypin's lessons and with the undeviating and consistent agitation of revolutionary Social-Democrats there will surface inevitably more and more steeled fighters who do not just come from the socialist proletariat but also from the democratic masses of the peasantry, and these will be less prone to fall into our historical sin of Tolstoyism!

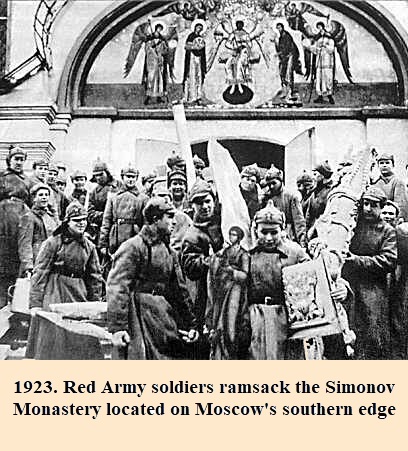

The Bolsheviks were in earnest. An Eighth Department with the unofficial name of "Liquidation" was added to the People's Commissariat of Justice. The department confiscated church property and applied the most brutal repression on resisting laity and clergy.

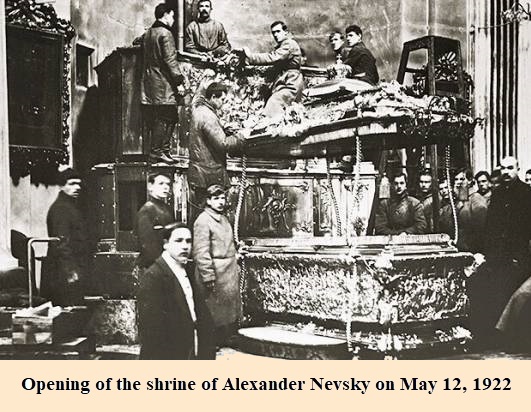

A popular practice of the day was to open the catafalques of saints and to display their contents to demonstrate that so-called saints were not so incorruptible after all. The underlying message broadcast upon a normal outcome was, "Citizens, watch how the churchmen are deceiving you." This routine became official policy on February 16, 1919, when the People's Commissariat of Justice issued a decree encouraging the ritual. A sidenote scribbled on the draft of the document explained,

The opening of catafalques must be welcomed since all cases show, as expected, the absence of "relics" and simultaneously unveil for everyone to see the age-old deception of the clergy together with the manipulation of the religious feelings of the naive and ignorant masses by the exploiting class.

The cult of incorruptible corpses had reached enormous proportions in the Russian Orthodox Church—and it is important to emphasize the word "incorruptible" here. When the evidence absolved the thesis, as happened in a number of cases, the mummy inside the sarcophagus was shipped quietly away to stowage in some museum or other. Otherwise the Bolsheviks showcased "the deceptive ways of the churchmen" at an autopsy.

It turned out that the silver tombs, often glittering with precious stones, contained either decayed bones reduced to dust or iron armatures wrapped in fabric, women's stockings, boots, gloves, cotton wool, flesh-colored cardboard, etc.

(Pyotr Krasikov, Eighth Department head and editor-in-chief of the magazine Revolution and the Church)

Lenin relied on the Marxist postulate that the laity would shun a church deprived of its material assets. In the event things did not quite turn out so simple. Vladimir Ilyich admitted in a conversation with Bonch-Bruyevich that the creation of a new Soviet man is not a quick process based on enlightening the befogged masses. His opinion was reflected in the thirteenth point of the programme of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) which states in part,

The Party strives for the complete destruction of the connection between the exploiting classes and the organization of religious propaganda, promoting the actual liberation of the working masses from religious prejudices and organizing the broadest scientific-educational and anti-religious propaganda. At the same time it is necessary to carefully avoid any insult to the feelings of believers, which only leads to the buttressing of religious fanaticism.

The last line seems quite comical considering that the programme was adopted in March 1919 when the campaign to open catafalques and confiscate church property was already in full swing.

Initially the switch from "War Communism" to the "New Economic Policy" had no effect on Bolsheviks' attitude toward the church.

A striking illustration is Lenin's letter to the Politburo dated 1922. In it he expresses his thoughts on the events in the town of Shuya where believers firmly resisted the Bolsheviks' attempt to expropriate church valuables,

One intelligent writer on state affairs rightly said that if it is necessary to resort to a series of cruelties in order to achieve a certain political goal, then they must be carried out in the most energetic manner and in the shortest possible time.

He then proposed sending "one of the most energetic, intelligent and efficient members of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee" to Shuya to carry out the arrests of "as many as possible" representatives of the local clergy, bourgeoisie and petty bourgeoisie.

On his return from Shuya the selected comrade went to Moscow and gave an oral (precisely oral) directive to the judges who subsequently sentenced to death "a very large number of the most influential and dangerous Black Hundreds in the city of Shuya, and if possible, not only in this city, but also in Moscow and several other spiritual centers." The referenced letter is of course marked, "Top Secret."

The suppression of the Shuya riots became one of the last chapters in the history of the first Soviet anti-religious wave.

The groundwork for a new "assault on Heaven" began in 1922 with the publication of the newspaper Atheist and the attempts to build an anti-religious group around it.

Russian sources: Mikhail Karpov's Inside-out Christianity and Alexandra Guzeva's How the Bolsheviks Destroyed the Russian Orthodox Church.

3. ON THE ROAD.

A year of disintegration, a year of ideological and political disunity, a year of Party driftage lies behind us. The membership of all our Party organizations has dropped. Some—namely those whose membership was least proletarian—have fallen to pieces. The Party's semi-legal institutions created by the revolution were smashed time after time. Things reached a point where some elements in the Party, under the impact of the general collapse, began to ask whether it was necessary to preserve the old Social-Democratic Party, whether it was necessary to continue its work, whether it was necessary to go "underground" once more, and how this was to be done. And the extreme Right (the liquidationist trend, so called) answered this question saying that it was necessary to legalize ourselves at all costs, even at the price of an open renunciation of the Party programme, tactics and organization. This was undoubtedly an ideological, political and organizational crisis.

The recent All-Russian Conference of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party 1 has set the Party on the right path and evidently marks a turning-point in the evolution of the Russian working-class movement after the counter-revolution's triumph. The decisions of the conference, published in a special Report issued by the Central Committee of our Party, were ratified by the Central Committee and therefore stand as the decisions of the whole Party until the next Congress.2 These decisions give a very definite answer to the question of the causes and the significance of the crisis, as well as the means to overcome it. By working in the spirit of the conference resolutions, by striving to make all Party workers realize clearly and fully the present tasks of the Party, our organizations will be able to strengthen and consolidate their forces for united and effective revolutionary Social-Democratic work.

The main cause of the Party crisis is indicated in the preamble of the resolution on organization. This main cause is the wavering intellectual and petty-bourgeois elements which the workers' party had to rid itself of; elements who joined the working-class movement mainly in the expectation of an early triumph of the bourgeois-democratic revolution and who could not stand up to a period of reaction. Their instability was shown both in theory ("retreat from revolutionary Marxism") in tactics ("whittling down of slogans") and in the Party organization. The class-conscious workers rejected this instability, came out resolutely against the liquidators, began to take the management and guidance of the Party organizations into their own hands. If this hard core of our Party was unable to overcome the elements of disunity and crisis at the outset, this was not only because the task was a great and difficult one amidst the triumph of the counter-revolution, but also because a certain indifference towards the Party emerged among those workers who, though revolutionary-minded, were not socialist-minded enough. The decisions of the conference address primarily the class-conscious workers of Russia and represent the crystallized opinion of Social-Democracy on combating disunity and vacillation.

[...]

We must excel this stage. Present conditions require new forms of struggle. Use of the Duma tribune is an absolute necessity. A prolonged effort to educate and organize the proletarian masses becomes particularly important. The combination of illegal and legal organization raises special problems. Popularization and explanation of the experience of the revolution which liberals and liquidationist intellectuals are seeking to discredit are necessary for theoretical and practical purposes. But the tactical line of the Party, which must acknowledge the new environment in its methods and ways of struggle, remains unchanged. The correctness of revolutionary Social-Democratic tactics—states a conference resolution—is confirmed by the experience of the mass struggle in 1905-07. The defeat of the revolution's first campaign revealed not that the tasks were wrong, not that the immediate goals were "utopian" or methods and means mistaken, but that the forces were insufficiently prepared, that the revolutionary crisis was not wide and deep enough—yet Stolypin & Co. are working to widen and deepen it with most praiseworthy zeal! Let liberals and terrified intellectuals lose heart after the first genuine mass battle for freedom, let them repeat like cowards: don't venture where you were mauled, don't tread that lethal path again. The class-conscious proletariat will answer them: the great wars in history, the great difficulties of revolutions, were solved only by the advanced classes returning to fight again and again—and they achieved victory after learning the lessons of defeat. Defeated armies learn well. The revolutionary classes of Russia were defeated in their first campaign, but the revolutionary environment persists. In novel forms and on new routes—sometimes much more slowly than wished—another revolutionary crisis approaches and comes to a head. We must persevere with the lengthy work of preparing bigger masses for that crisis. The preparation must be soberer, assume loftier and clearer tasks; and the more successfully we do this work, the more certain will our victory be in the new struggle. The Russian proletariat can be proud of the fact that under its leadership in 1905 a nation of slaves became a million-strong host for the first time, a revolutionary army striking at tsarism. And now that same proletariat will know how to educate and train persistently, staunchly, patiently, the new cadres of an even mightier revolutionary force.

4. THE ATTITUDE OF THE WORKERS' PARTY TO RELIGION: 1930 SOVIET FILM CLIP.

5. THE ATTITUDE OF THE WORKERS' PARTY TO RELIGION.

Social-Democracy bases its whole world-outlook on scientific socialism, i.e., Marxism. The philosophical basis of Marxism, as Marx and Engels declared repeatedly, is dialectical materialism, appropriating fully the historical traditions of eighteenth-century French materialism and of Feuerbach in Germany (first half of the nineteenth century)—a materialism wholly atheist and positively hostile to all religion.

[...]

Marxism is materialism. As such it is as relentlessly hostile to religion as was the materialism of eighteenth-century Encyclopaedists or the materialism of Feuerbach. This is beyond doubt. But the dialectical materialism of Marx and Engels goes farther than the Encyclopaedists and Feuerbach for it applies materialist philosophy to the domain of history, to the social sciences' domain. We must combat religion—that is the ABC of all materialism and consequently of Marxism, but Marxism does not halt at the ABC. It steps past.

Marxism says: We must know how to combat religion, and in order to do so we must explain the source of faith and religion among the masses in a materialist way. The combat against religion cannot be confined to abstract ideological preaching, and it must not be reduced to such preaching. It must adhere to the class movement that strives to eradicate the social roots of religion.

Why does religion retain its hold on the backward sections of the town proletariat, on broad sections of the semi-proletariat and on the mass of the peasantry? Because of the ignorance of the people, replies the bourgeois progressive, the radical or the bourgeois materialist. And so: "Down with religion and long live atheism; the dissemination of atheist views is our chief task!" The Marxist says this is not true, this is the superficial view of narrow bourgeois uplifters. It does not explain the roots of religion radically enough; it explains them in an idealist, not materialist, fashion. In modern capitalist countries these roots are mainly social.

The deepest root of religion today is the socially downtrodden condition of the working masses and their apparent helplessness in the face of the blind forces of capitalism which every day and every hour inflicts the most horrible suffering and the most savage torment upon ordinary working people, a suffering a thousand times worse than those inflicted by extraordinary events like wars, earthquakes, etc. "Fear made the gods." Fear of the blind force of capital—blind because the masses do not see its motivation—a force which at every step in the life of the proletariat or small owner does or threatens to inflict "sudden" "unexpected" "accidental" ruin, wreck, pauperism, prostitution, starvation—such fear is the root of modern religion which the materialist must bear in mind first and foremost if he does not wish to stay a primary-school materialist.

No educational book can eradicate religion from the minds of masses who are crushed by capitalist hard labour, who are at the mercy of the blind destructive forces of capitalism, until the masses themselves learn to fight this root of religion, fight the rule of capital in all its forms, in a joint, organized, planned and conscious way.

Does this mean that educational books disparaging religion are harmful or unnecessary? No, nothing of the kind. It means that Social-Democracy’s atheist propaganda must be subordinated to its main task: fostering the class struggle of the exploited masses versus the exploiters.

This proposition may not be understood (at least not immediately) by someone who has not pondered over the principles of dialectical materialism, i.e., the philosophy of Marx and Engels. How is that?—he will say. Is ideological propaganda, the preaching of definite ideas, the struggle against that enemy of culture and progress which has survived for thousands of years (i.e., religion) to be made subordinate to the class struggle, i.e., to the struggle for concrete goals in the economic and political sphere?

This is one of those current objections to Marxism which testify to a complete misunderstanding of Marxian dialectics. The contradiction which perplexes these objectors is a real contradiction of real life, i.e., a dialectical contradiction, not an artificial one.

To draw a hard-and fast line between theoretical propaganda of atheism among certain sections of the proletariat and the success, progress or stage of their class struggle is to reason undialectically, to transform a shifting, hazy boundary into an absolute one; it is to sunder what is indissolubly coupled in real life.1

Let us take an example. Let us assume that the proletariat of a particular region and industry is divided between an advanced section of fairly class-conscious Social-Democrats, who are of course atheists, and rather backward workers connected still to the countryside, to the peasantry, and who believe in God, go to church or, let us suppose, are influenced by a local priest organizing a Christian labour union.2 Let us moreover assume that the economic struggle in this locality has triggered a strike. It is a Marxist's duty to rank the strike's success above all else, to vigorously offset and oppose a split of workers into atheists and Christians. Atheist propaganda in such circumstances may both be unnecessary and harmful, not from a philistine fear of scaring away the backward sections or of losing a seat in the elections and so on, but out of consideration for nourishing the class struggle which in modern capitalist society will convert Christian workers to Social-Democracy and atheism a hundred times faster than bald atheist propaganda. To preach atheism under such circumstances would only play into the hands of the priest or priests who love nothing more than replacing a split of strikers and strikebreakers with a split of Christian and atheist strikers. An anarchist who preached war against God at all costs would in effect be helping the priests and bourgeoisie (as anarchists always do in practice). A Marxist must be a dialectical materialist and treat the struggle against religion not on an abstract basis—arcane theories, invariant preaching—but on the practical basis of the class struggle which educates the masses better than anything else can. A Marxist must be able to pan a given situation fully, to discern the boundary (hazy, variable but real) between anarchism and opportunism. And he must not succumb either to the abstract hollow "revolutionism" of the anarchist or the philistinism and opportunism of the petty bourgeois or liberal intellectual who, forgetting his duty, boggles at the struggle against religion, reconciles himself to belief in God and is led not by the interests of the class struggle but by the petty mean attitude of not offending, repelling or frightening anyone away, as in the saw: "Live and let live", etc., etc.3

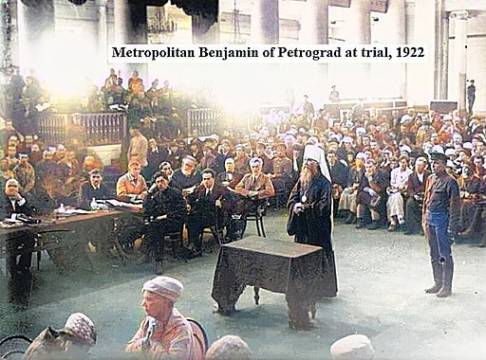

In the summer of 1917 a large church council called the Patriarchate reopened in Moscow and elected Patriarch Tikhon. He condemned the shedding of blood during the Russian Civil War and appealed for a change of heart. He was arrested briefly in 1922 and released after allegedly confessing his exposure to anti-Soviet ideology and vowing that he was “no longer an enemy of Soviet power.” Priests loyal to the Bolsheviks denounced him and he was eventually deposed. This deed effectively beheaded the Russian Orthodox Church.

In 1918 came the Bolshevik decree, "On the separation of the Church and the State and of the School from the Church." Church lands were confiscated, marriage and family relations secularized.

Between 1918-20 the Marxists launched an anti-religion campaign which included the blasphemous opening of reliquaries of renowned Russian saints in order to disprove their incorruptibility and quash their veneration. State propaganda carried photographs of the opened reliquaries.

In 1922 the Bolsheviks marched further afield and initiated a campaign to confiscate church valuables under the pretext of fighting mass hunger and restoring the economy destroyed by the Civil War. Any church item suspected of harbouring or displaying gold, silver or precious stones was brought from the entire country to a special state repository. Much of the loot was subsequently sold to the West.

Cheka police officers arrested priests who put up an active resistance to the barbaric looting of their churches. They charged the clerics with engaging in counter-revolutionary activity and with spreading anti-Soviet propaganda. The Chekists tortured and repressed them. More than a thousand priests suffered this persecution during the early 1920s, among them the Bishops of Moscow and Petrograd.

One of the most "high-profile" cases took place in the city of Shuya, Ivanovo region. Resurrection Cathedral parishioners assembled to thwart the removal of the church valuables. The Red Army fired on the crowd, killing several believers. Local priests were arrested, put on public trial, sentenced to death and shot.

Some clergy emigrated after the October Revolution but the majority stayed in Russia and continued to conduct services.

Russian source: Alexandra Guzeva's How the Bolsheviks Destroyed the Russian Orthodox Church.

Photo Colorizer: The original black-and-white photograph of Metropolitan Benjamin on trial at Petrograd is found on Alexandra Guzeva's webpage. The coloured version seen here was generated by Hotpot's Artificial Intelligence Picture Colorizer with a colorization factor of 18. "Hotpot" is the name of a private company founded in the year 2019.

2 Pope Gapon comes to mind (Chapter 6, Items 10-11).

3 Here Lenin sincerely warns the reader that Marxism is "relentlessly hostile to religion" and elsewhere Lenin brands religion "one of the most odious things on earth" (Item 2). Religious believers must heed his warning and abstain from alliances with Marxists because the materialist basis of Marxism will compel them sooner or later to eradicate religion always.

6. FROM RUSSIA.

St. Petersburg: Seven conspirators against the life of Grand Duke Nicholas were hanged on the Peter and Paul Fortress gallows recently. Two were women. One was a Polish Jew who passed himself off as an Italian named Calvino whose documentation he had pinched. The plotters had planned to hurl a dynamite bomb into the Imperial Council Salon as Mr. Stolypin read the ministerial declaration.

Poverty is on the increase. There are thousands of naked children in Kazan Province and the same is true of Smolensk; the number of deaths from starvation is substantial.

St. Petersburg: The Czar has pardoned twenty thousand convicts serving time in Siberia or in the jails of the Empire.

Moscow: The river (Moscova) has flooded a great portion of the city, leaving fifty thousand inhabitants homeless.

St. Petersburg: The devastation caused by the floods is enormous. The tilling fields of many gubernias have become lagoons, and creeks torrents carrying tree trunks and carcasses. The rising water has spoiled the grain stored in silos.

St. Petersburg: A stormy Duma session yesterday brought on by the reaction of leftists to Guchkov's accusation of filibuster.

St. Petersburg: The jurisprudence magazine Pravo has tallied 1650-1700 executions after promulgation of the law of speedy court martials on September 2, 1906. The tally implies an average number of ninety executions per month.

St. Petersburg: Heavy snowfall hampers the farming chores.

St. Petersburg: Health authorities are alarmed at the high incidence of smallpox in the city; on average twelve patients succumb daily.

St. Petersburg: There is growing revulsion across the Empire toward the rate of executions, not less than six a day.

St. Petersburg: Today (September 20) three hundred and ninety-eight new cases of cholera were recorded, a hundred and sixteen fatal.

St. Petersburg: The cholera epidemic is waning; ninety-eight patients died of cholera today (October 1).

St. Petersburg: The government is underreporting the true extent of the cholera epidemic. "During last week's Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday five hundred cholera victims were buried in one graveyard alone" (Morning Leader). There is a widespread exodus from the capital.

St. Petersburg: Between ten to fifteen cases of contagion are reported daily. The number of cholera patients admitted to hospital since the start of the epidemic is eight thousand seventy-six. Three thousand two hundred and ninety succumbed. The number of recovery cases is four thousand six hundred and eight.

St. Petersburg: Nine terrorists were executed, many more wait on death row.

The cholera epidemic has worsened dramatically.

Moscow: A terrorist organization of thirty members has been detained; they had a clandestine printing press. The terrorists inside the building hurled grenades at fifty policemen who surrounded the house, then at the troops who took over from the police and finally at the artillerymen who replaced the troops. After twenty hours of fierce combat the firefight ceased, leaving a hundred and fifty casualties between dead and wounded.

St. Petersburg: Last night a stranger dressed like a student entered a café and hurled a bomb causing a lot of damage but no casualties owing to the small number of customers present.

St. Petersburg: A conspiracy to assassinate the Czar has been uncovered at his palace.

St. Petersburg: The Russian Empress has donated a hundred thousand rubles to victims of the Italian earthquake.

St. Petersburg: Some cases of cholera, most of them fatal, were reported in the city yesterday.

St. Petersburg: Revolutionaries and mere suspects are executed "without pause"; energetic protests were raised at the Duma about these "unnecessary and wholly unjustifiable" measures.

A Duma deputy has apparently proposed abolishing the death penalty. Two thousand eight hundred and thirty-five persons have been executed over the past three years.

The Russian Interior Ministry has published its official figure of five and a half million Jews living across the Empire. Poland houses a million eight hundred thousand, Odessa a hundred and eighty thousand and Warsaw thirty thousand.

St. Petersburg: Stolypin is near death. The Minister of Finance has taken over the presidency of the government.

Tolstoy's illness has remitted; he is no longer bedridden although he is unable to walk about.

St. Petersburg: Stolypin has returned to the capital from Crimea fully recovered.

St. Petersburg: Russia recorded ten thousand four hundred and twenty cases of cholera and four thousand deaths over the past week.

A locomotive engineer went mad and drove his train at full speed without stopping at the stations; he tried to stab the coal stoker; the train's foreman rushed to the locomotive and brought it to a full stop but had to endure a tremendous stabbing spree from the crazed engineer.

St. Petersburg: The tram strike has turned into a general strike. City Hall fired three thousand five hundred employees who refused to work this morning. Some forty trams circulate. Troops will drive the trams if the strike continues.

Kovno (Lithuania): Stolypin received in audience an Israelite commission that came to solicit an improvement in the welfare of Russian Jews. The Minister acknowledged the justice of their petition but added that the role played by Jews in domestic politics precluded a favourable resolution of their request.

| And Now For Something Completely Different |