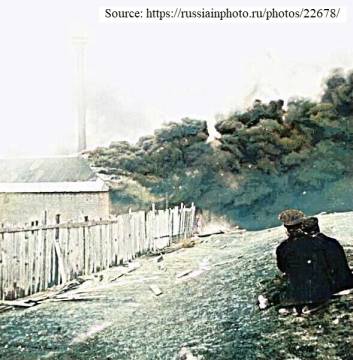

May 11, 1909. The devastating fire of Novonikolaevsk

Sources: webpage and Lunapic

1. L. N. TOLSTOY AND THE MODERN LABOUR MOVEMENT.

Russian workers in practically all the large cities of Russia have already responded in one way or another to the death of L. N. Tolstoy the writer who produced a number of most remarkable works of art that rank him among the great writers of the world and the thinker who with immense power, self-confidence and sincerity raised a number of questions concerning the basic features of the modern political and social system. All in all, their response was printed in the newspapers and conveyed by the labour deputies of the Third Duma via telegram.1

L. Tolstoy began his literary career when serfdom still existed but had obviously reached its final days. His main activity spans two turning points of Russian history, 1861 and 1905. Traces of serfdom survived throughout the economic and political life of the country, particularly in the countryside, but capitalism, implemented from above, flourished among the lower rungs of society.

How did the survivals of serfdom manifest in mainly agricultural Russia? Most and clearest of all in the fact that agriculture was driven by a ruined impoverished peasantry toiling with antiquated primitive methods on old feudal allotments mapped out in 1861 for the benefit of the landlords. And, on the other hand, agriculture was driven by landlords who in Central Russia cultivated the land with the labour, wooden ploughs and horses of the peasants in return for segregated plots of land, meadows, access to watering-places, etc. To all intents and purposes this was still the old feudal economy. Feudalism also permeated the political life of Russia. This was shown by the constitution of the state prior to 1905, by the ascendancy of the landed nobility in state affairs and by the unlimited power of officials, most of whom came from the landed nobility particularly in the higher ranks.

However this old patriarchal Russia began to disintegrate rapidly after 1861 under the influence of world capitalism. Peasants were starving, dying, destitute as never before, fleeing to the towns and abandoning the soil. There was a boom in the construction of railways, mills and factories thanks to "cheap labour" supplied by the displaced peasants. Big finance capital, large-scale commerce and industry were taking hold in Russia.

It was this swift, painful, dramatic demolition of the old "pillars" of old Russia that Tolstoy the artist reflected in his works and that Tolstoy the thinker co-opted in his views.

Tolstoy had a surpassing knowledge of the lifestyle of landlords and peasants in rural Russia. In his artistic oeuvre he gave descriptions of this life that are numbered among the best works of world literature. The drastic demolition of all the "old pillars" of rural Russia sharpened his focus, riveted his interest in what was going on around him and led to a radical change in his whole world outlook. By birth and education Tolstoy belonged to the highest landed nobility of Russia, but he broke with all the conventions of his class and in his latter works criticized fiercely all contemporary state, church, social and economic institutions founded on the enslavement of the masses, their poverty, on the ruin of peasants and petty proprietors, on the coercion and hypocrisy that permeated life from top to bottom.

Tolstoy's criticism was not new. He said nothing that had not been said long before in both European and Russian literature by friends of the working people. But the uniqueness of Tolstoy's critique and its historical significance lie in the fact that it conveyed with the power possessed only by artists of genius the radical shift in the thinking of the masses in rural peasant Russia.

Tolstoy's criticism differs from the criticism of the same institutions made by representatives of the modern labour movement in that his standpoint was the patriarchal naïve peasant's whose psychology Tolstoy co-opted into his doctrine. Tolstoy censures with great emotion, passion, conviction, freshness, sincerity and fearlessness in "going down to the roots" of why the masses are so afflicted. He echoes the sharp turn in the minds of millions of peasants who liberated from feudal bondage discover the new horrors of destitution, death from starvation, urban homelessness, and so on and so forth. Tolstoy mirrored their sentiments so faithfully that he imbibed their naïveté, their political alienation, their mysticism, their desire to abscond from the world ("non-resistance to evil") their impotent deprecations of capitalism and of the "power of money." The protest and despair of millions of peasants steep Tolstoy's doctrine.

The representatives of the modern labour movement find they have plenty to protest about but nothing to despair over. Despair is typical of perishing classes, but the wage-workers' class is growing inevitably, evolving and strengthening in every capitalist society, Russia included. Despair is typical of those who do not understand the roots of evil, see no way out and can not struggle. The modern industrial proletariat does not fit in that category.

2. L. N. TOLSTOY.

Tolstoy is dead and pre-revolutionary Russia, whose weakness and impotence are transcribed in the philosophy and works of the great artist, has become a thing of the past. But his heritage includes what has not become a thing of the past but belongs to the future. This heritage is accepted and being elaborated by the Russian proletariat.

The Russian proletariat will explain to the masses of toilers and exploited the meaning of Tolstoy's criticism of the state, the church, the private ownership of land—not in order that they should confine themselves to self-perfection and yearning for a godly life, but in order to deal a new blow to the tsarist monarchy and landlordism which were but slightly damaged in 1905 and which must be destroyed.

The Russian proletariat will explain to the masses Tolstoy's criticism of capitalism—not in order that they should confine themselves to hurling imprecations at capital and the rule of money, but in order to learn how to use the technological and social accomplishments of capitalism at every stage of their life and struggle to weld themselves into an army of millions of socialist fighters who will overthrow capitalism and create a new society where people will not be doomed to poverty and where there will be no exploitation of man by man.

3. TOLSTOY AND THE PROLETARIAN STRUGGLE.

Tolstoy's indictment of the ruling classes was made with tremendous power and sincerity. He laid bare with absolute clarity the immanent falsehood of all institutions that sustain modern society: the church, the law courts, militarism, "legal" wedlock, bourgeois science. But his doctrine proved to be in total contradiction with the life, toil and struggle of the proletariat, that grave-digger of modern society. Whose then was the point of view reflected in the teachings of Leo Tolstoy? Through his pen spoke that host of Russians who already detest the masters of modern life but have not yet attained to intelligent, coherent, complete, implacable struggle against them.

The history and outcome of the great Russian revolution have shown that said host crammed the space between the class-conscious socialist proletariat and the brazen defenders of the old regime. This host composed mainly of peasants showed in the revolution how much it hated the old regime, how keenly it felt the abuses of the new one and attested its great yearning to be rid of both and find a better life. Yet the host also demonstrated in the revolution little political awareness, vagary and diminished ambition in the quest for a better life.

This great human ocean, stirred to its very depths, with all its weaknesses and strengths, washed in the doctrine of Tolstoy.

By studying the literary works of Leo Tolstoy, the Russian working class will be better acquainted with its enemies; by examining his doctrine the whole Russian people will discover what weakness of theirs frustrated their emancipation. This must be understood in order to take a step forward. But this forward step is haltered by everybody who makes Tolstoy out to be the "universal conscience" or a "teacher of life." This is a lie deliberately bandied about by liberals who handle the anti-revolutionary aspect of Tolstoy's doctrine to their advantage, and some former Social-Democrats echo these liberals.

The Russian people will secure their emancipation only when they learn how to gain a better life not from Tolstoy but from the class whose significance he did not grasp and which alone is capable of destroying the old world he loathed. That class is the proletariat.

4. THE BEGINNING OF DEMONSTRATIONS.

After three years of revolution (1905-1907) Russia went through three years of counter-revolution, of the Black-Hundred Duma: an orgy of violence and suppression of rights, a capitalist offensive against workers and the retraction of their gains.

The tsarist autocracy, semiruined in 1905, has mustered its forces, has shaken hands with landlords and capitalists in the Third Duma and has re-introduced the old order of things in Russia. Harsher than ever the capitalist oppression of workers, bolder than ever the lawlessness and tyranny of the officials in towns and especially in the countryside, more ferocious than ever the reprisals against the champions of freedom, more frequent than ever the application of the death penalty. The tsarist government, landlords and capitalists took furious revenge on the revolutionary classes—on the proletariat above all—as if rushing to take advantage of the lull in the mass struggle. But there are enemies who can be defeated in battle after battle, who can be suppressed for a time yet cannot be eradicated. A complete victory of the revolution is entirely possible which would destroy the tsarist monarchy utterly, sweep the feudal landlords off the face of the earth, transfer their land without compensation to the peasantry, substitute officialdom with democratic self-government and political freedom. These reforms are indispensable in the twentieth century. They have already been realized more or less in all the states of Europe following a more or less protracted persistent struggle.

But no reactionary victory, however complete, no triumph of the counter-revolution can crush the foes of the tsarist autocracy, the enemies of landlord and capitalist oppression, because those foes, whose numbers grow constantly, are the workers in their millions assembled in towns, big factories or the railways. Enemies too are the destitute peasants whose life became many times harder since rural superintendents and rich peasants banded together for legalized plunder, appropriating land with the sanction of the landlords' Duma and with police and military protection. Foes like the working class and the poor peasantry cannot be obliterated.

And presently after three years of the most wanton riot of counter-revolution we see that masses of the most downtrodden, the oppressed, the benighted, those intimidated through every type of persecution, are beginning to lift their heads, reawaken and resume the struggle. Three years of executions, persecution and savage reprisals eliminated tens of thousands of the autocracy's enemies, hundreds of thousands were jailed or exiled, many more intimidated.1 But millions and tens of millions no longer are what they were before the revolution. Never before had they experienced such instructive and vivid lessons of open class struggle. This summer's strikes and the recent demonstrations show that a new round of active fermentation has bubbled up among them.

Russian worker strikes during both the pre- and the revolutionary periods were the most common tool of struggle handled by the proletariat, the only advanced, consistently revolutionary class of modern society. The economic and the political strikes, disjoint or meshed, fused the workers together in a fight against the government and the capitalist class, fermented society and roused the peasantry for the struggle.

A wave of continuous strikes begun in 1895 marked the start of the pre-revolutionary period. The actual revolution began when the number of strikers topped 400,000 in January 1905. Over the next three years the tally beat all records anywhere. Still it dipped progressively from its 1905 maximum (almost three million strikers) through 1906 (a million) to 1907 (three quarters of a million).

The first revolution—or rather the first phase of the revolution—finished when the number of strikers plunged to 176,000 in 1908 and plummeted to 64,000 in 1909.

And now the tide has begun rising again since this summer. The number of participants in economic strikes is increasing and increasing very fast. The domination of the Black-Hundred reaction is over. A new upsurge begins. The proletariat which mostly receded in 1906-1909 is reviving and starting to take the offensive. An economic uptick in the industrial sector triggers an immediate revival of the proletarian struggle.

The proletariat has set forth. Others like the bourgeois, democratic classes and segments of the population follow. The death of Muromtsev the Chairman of the First Duma, a moderate liberal, a foreigner to democracy, provokes the first timid demonstrations. The death of Leo Tolstoy sparks the first street demonstrations mainly of students but partly also of workers. The fact that quite a number of factories and plants ceased operations on the day of Tolstoy's funeral marks the start of demonstrative strikes, albeit a very modest one.

Very recently the atrocities of the tsarist gaolers who in Vologda and Zerentui 2 tortured many comrades jailed for their heroic struggle in the revolution have agitated the students further, holding assemblies and mass meetings all over Russia. The police raid the universities, beating, arresting students, prosecuting newspapers for publishing the smallest particle of truth about the disorders, but only aggravating the unrest by all these actions.

The proletariat has set forth. Democratic youth follows. The Russian people awaken to a new struggle and stride toward a new revolution.

The outset of the struggle has shown us once more that the forces which shook the tsarist regime in 1905 are alive and will crush it in the coming revolution. The outset of the struggle has shown us once more the importance of the masses. No persecution, no reprisal can halt their movement once millions of people uprise. Persecution merely pours oil on the flames, enlists new contingents of fighters to combat. No terrorist act aids the oppressed masses and no power on earth can halt them when they revolt.3 Now they have set forth. The upsurge may be quick or slow and fitful but it leads to revolution either way.

The Russian proletariat led the way in 1905. Remembering this glorious past it must now exert every effort to restore, reinforce and renew its organization, its Party, the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party. Although our Party is going through difficult days it is invincible like the proletariat.

So get to work, comrades! Get busy everywhere organizing, creating, reinforcing Party units of Social-Democratic workers and intensifying the economic and political agitation. In the first Russian revolution the proletariat taught the masses how to fight for freedom, in the second it must lead them to victory!

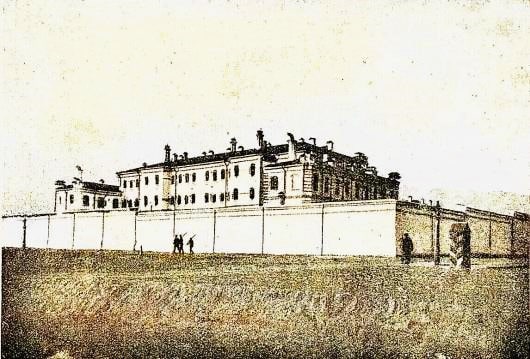

2 In 1910 the Gorno-Zerentui Prison was encircled by a high brick wall and sentry boxes. Many soldiers kept guard. Built for a population of three hundred inmates the jailhouse was overcrowded as a matter of course (899 convicts in 1908, 628 convicts in 1910). It had a bakery and a kitchen. Regular criminals occupied the first floor, criminals and political prisoners filled the second.

Hundreds of political prisoners passed through Gorno-Zerentui between the years 1905 and 1917. A significant number of inmates was made up of professional revolutionaries. The Socialist-Revolutionary Party group was the most numerous. Next in line came the Social-Democratic Party group which usually collaborated with the Socialist-Revolutionaries on the most important issues. There were also anarchists, Bundists, Polish Social-Democrats of various stripes and members of a Baltic opposition group called the "Forest Brothers."

Political prisoners spanned the full class spectrum from simple peasants to the nobility; the workers and the peasants in soldier or sailor uniform were the most numerous. The petty bourgeoisie were represented by government employees, businessmen and shopkeepers. There were also a few intellectuals and students.

From May 9 to 20, 1910, a survey of the penal system was conducted by General Putilov the Ataman of the Third Regiment of the Transbaikal Cossack Army.

Below are excerpts from his report,

Out of six hundred and twenty-eight inmates at Zerentui a hundred and forty-eight are political prisoners. Twenty-three of these are in solitary confinement and one is in a darksome punishment-cell. Political prisoners may or may not share living quarters with criminal convicts. No personal underwear, clothes or shoes were found on the inmates except in two instances. Unlike criminal convicts political prisoners do not work outdoors. "You" is the informal address reserved for them. The reading materials available are administered by the prison head. The political prisoners are allowed to read outdated newspapers at least a year old by order of the Transbaikal Region military governor.

Putilov reports the following deficiencies: lack of ventilation in the cells during the winter, tattered bedding, inappropriate bathing facility, overcrowded cells and 40% of inmates had contracted tuberculosis. Nevertheless Putilov concludes that Gorno-Zerentui Prison complies with official regulations. It was considered the best one of the penal circuit. The regime of detention at Zerentui was quite liberal during 1905-1910. The cells were unlocked, inmates could stroll about freely. Many inmates wore casual clothes, they had an opportunity for self-education and they did not wear legcuffs.

Russian sources: A. Simatov's In the Gorno-Zerentui penal prison (1905-1910) and L. Vsevolod's Daring Escapes from Nerchinsk Penal Servitude. The Self-Proclaimed Tsar, the Decembrist Lieutenant, and the Singer.

3 "No terrorist act aids the oppressed masses" contravenes Lenin's stance on Items 3-4 of Chapter 9 and Item 9 of Chapter 7. Lenin judged isolated terrorist attacks like those of the Socialist-Revolutionaries worthless, but he certainly advocated fusing terrorism with an uprising of the masses (Chapter 6, Item 8).

5. WHAT IS HAPPENING IN THE COUNTRYSIDE?

Ex-Minister of Agriculture Yermolov's new book about the "present epidemic of arson in Russia" has given rise to controversy in the newspapers. The liberal press has pointed out that arson in the countryside increased after the 1905 Revolution. Reactionary newspapers echo Yermolov's outcry and lamentation about the "impunity of the arsonists," the "terrorism in the countryside," and so on.

There has been an extraordinary increase in the number of rural fires. For instance between 1904 and 1907 the figure rose twofold in Tambov Gubernia, two and a half times in Orel Gubernia and threefold in Voronezh Gubernia.

"The more or less well-to-do peasants," writes Novoye Vremya, a lackey of the government, "want to set up farmsteads and are trying to introduce new farming methods but are besieged, as it were, by guerrillas in enemy territory, by a lawless rural element that has run wild. They are being burned out and hounded, hounded and burned out, until there is nothing left for them to do but 'abandon everything and flee.'"

An unpleasant admission indeed for those supporting the tsarist government! For us Social-Democrats the latest information holds interest as further confirmation of governmental lying and pitiful impotence of liberal policy. The liberal plan to "reconcile" peasants with landlords through "redemption payments at a fair valuation" was an empty, miserable, treacherous trick.

The Revolution of 1905 showed fully that the old order of the Russian countryside is irrevocably doomed by history. Nothing in the world can bolster it up. How is it to be changed? The peasant masses gave the answer with their uprisings in 1905 and with their deputies of the First and Second Dumas, namely, the landed estates must be snatched from the landlords without compensation. When thirty thousand landlords (headed by Nicholas Romanov) own 70 million dessiatines of land and ten million peasant households own nearly the same area, the result can only be bondage, abject poverty, ruin, stagnation of the whole national economy.1 Hence the Social-Democratic Labour Party called on peasants to revolt. Russian workers rallied and directed the peasants in 1905 with their mass strikes.

How does Stolypin's government want to refashion the old order of the countryside? It wants to speed up the complete ruin of the peasants, preserve the landed estates, help an insignificant handful of rich peasants to grab as much land from the village communes as possible and to build farmsteads.2 The government has realized that the peasant masses are against it and is trying to find allies among the rich peasants.

Stolypin himself once said that "twenty years of calm" would be needed to carry out the "reform" proposed by the government. By "calm" he means the submission of the peasants, the absence of violence. Yet his "reform" cannot be implemented without resorting to the violence of rural superintendents and other authorities against tens of millions at every step. The Stolypin "reform" cannot be enforced without quashing the smallest resistance. Not even for three years, let alone twenty, has Stolypin been able to bring about "calm" nor will he be able to do so. The tsar's lackeys were reminded of this unpleasant truth by the ex-minister's book about fires in the countryside.

Peasants have no way out of their desperate want, poverty and starvation...other than by joining with the proletariat to overthrow the tsarist regime. The immediate task of the R.S.D.L.P. is to prepare the proletariat for this action creating, growing and consolidating the proletarian organizations.

6. FROM RUSSIA.

St. Petersburg; Paris: A plot to assassinate the Czar has been uncovered. The plotters planned to infiltrate the police. Some members of Russian high society were involved.

St. Petersburg: The Czarina's illness has worsened noticeably; her death seems likely.

St. Petersburg: A cannon has gone missing from an artillery garrison. Several soldiers are being court-marshalled.

St. Petersburg: The inmates of "Skobelov" (?) Prison mutinied. Several guards were hurt, nine inmates perished and many others were wounded.

St. Petersburg: On the evening of September 25 the Northern Lights were distinctly visible over the capital. The same phenomenon was observed in Livonia. Violet tints predominated.

St. Petersburg: The Czar pardoned four death-row inmates.

St. Petersburg: A conspiracy against the Czar has been uncovered involving masons doing repair work at the Winter Palace.

The Czar has pardoned all death-row inmates linked to the 1905 (Old Style December) Revolution in Moscow.

St. Petersburg: The Czar will definitely visit Italy. The Czarina's health has improved noticeably.

St. Petersburg: The ceiling of a Duma chamber collapsed. No one was hurt.

The Duma celebrated the first session of its new seating today.

The Czar arrived to Rome.

St. Petersburg: The revolutionaries are apparently planning to use an airplane to assassinate the Imperial family. Consequently a no-fly zone has been established for a radius of 2 kilometers from the palace.

Krouptve (?): Three armed men broke into a birthday party and shot a priest and six men dead.

St. Petersburg: The Duma elected its President and Vice President in yesterday's session. The Social-Democrats and the Cadets abstained from voting. Khomyakov was elected President by 212 votes for, 93 against. Shidlovsky was re-elected Vice President.

Odessa: City Hall moved by a vote of 41 to 18 to petition the Czar to deny Jews the right to vote and to bar them from the Duma.

Definitive Russo-Japanese War Statistics: Mobilized: 1,365,000 Russians vs. 1,200,000 Japanese. Combatants: 590,000 Russians vs. 540,000 Japanese. Dead: 313,000 Russians vs. 392,000 Japanese. Cost of the war: 6,000,000,000 francs (Russia) vs. 4,500,000,000 francs (Japan).

St. Petersburg: A fierce blaze destroyed the palace of Grand Duke Nikolaevich. Very valuable collections of art and antiques were lost.

St. Petersburg: The Czarina is feeling extremely unwell. The physicians say that her condition is hopeless.

St. Petersburg: The Czarina had a fainting spell that lasted for one hour.

St. Petersburg: The health of the Czarina has improved considerably.

St. Petersburg: Snowstorms have caused many victims. Snowbanks are a meter tall in some places.

St. Petersburg: Intense cold. Many people froze to death on streets and in the countryside. Hungry wolves roam the outskirts of St. Petersburg. In several places bonfires are fed regularly to enable passersby to warm up. The theaters are vacant. The aristocratic salons have cancelled their parties. No one remembers such a hard winter.

The Rights tabled a law at the Duma depriving Jewish children of access to public school education and their parents from having careers as doctors, lawyers, teachers, members of the Army or civil servants.

Moscow: A cholera epidemic is causing many victims. The inhabitants of Russia's ancient capital flee terrified to other towns.

Sokolow (Poland): A blaze seared more than two hundred houses.

Moscow: A fire charred the electrical power station. No trams are running.

Porisso (?): A blaze destroyed an entire neighbourhood of four hundred and fifty houses. Arson is suspected.

Warsaw: A young terrorist hurled a bomb at Alexandrov the chief of police.1 Alexandrov was unhurt but his two companions perished. The terrorist committed suicide to avert arrest.

Warsaw, (Old Style) June 4 (via telegraph from our correspondent). On the Warsaw-Vienna platform of the Grodzisk Railway Station* a terrorist threw a bomb at the feet of Captain Aleksandrov the "Girardov" (?) police chief who was walking accompanied by two guards.** The bomb exploded with terrible force. The explosion wounded a guard seriously, slightly the other. Eight passengers were maimed. Aleksandrov survived miraculously and headed swiftly for the platform exit. Seeing this, the attacker ran after him and fired six shots from a Browning. Aleksandrov fell to the floor, wounded by six bullets. Gendarmes, soldiers and policemen who came running surrounded the assailant. He started singing the Varshavyanka, shot himself in the mouth and died on the spot. Aleksandrov was brought to Warsaw and taken to a hospital. His wounds are not fatal.

* According to Wikipedia Grodzisk is situated thirty kilometers southwest of Warsaw.

** According to the telegram Alexandrov is the head of the Zemstvo Guard.

Russian source: Newspaper Starosti.

This Captain Alexandrov is almost certainly the fellow mentioned by a letter sent to Felix Dzerzhinsky incarcerated between 1908 and 1909 at the Warsaw Citadel. Dzerzhinsky reproduces the letter in his prison diary entry for June 25, 1908. The sender was a comrade imprisoned in Ostrowiec, a metallurgical center situated 170 kilometers south of Warsaw. The letter mentions a certain Captain Alexandrov the chief of the Zemstvo guard in the Grójec District who was appointed chief of the secret police for the Ostrowiec District in May 1908.

This letter brands Alexandrov "the notorious inquisitor" [italics mine, EFC]. He used to flog suspects during interrogations,

Since Alexandrov’s wife was unable to bear the screams of the man who was being flogged, Szczesniak was taken late at night to a field on the outskirts of the town where he was stripped and beaten until he lost consciousness. Then, while still unconscious, he was taken to the punishment cell and dumped on the stone floor. The next day, taken to see Alexandrov once more, he persisted in his silence whereupon the flogging was repeated. Many others were subjected to the same torture. Adamski, a member of a local committee, was subjected to such mistreatment that he tried to smash his head against the wall but only succeeded in exacerbating his injuries. He was punished for this and handcuffed for three weeks.

Odessa: A thousand seven hundred and ninety-six new cases of cholera were registered last week. Seven hundred and nineteen were fatal. The peasants refuse to heed the doctors' quarantine orders.

The authorities in southern Russia have ordered the torching of hamlets to curtail the spread of the epidemic. Peasants are left in despair. Military physicians say that the onset of winter is the only remedy. Eighty-two thousand deaths have been registered across the Empire until now. It is presumed that the number will reach a hundred thousand in September.

Moscow: Two officers slew a policeman.

St. Petersburg: A voracious blaze in Tsaritsyn, southern Russia, destroyed two thousand houses. Thousands of families were left homeless. The dead number in the hundreds.1

The Sovereign Emperor has most graciously deigned to order that the Ministry of Internal Affairs be assigned ten thousand rubles to issue, on behalf of Her Imperial Majesty the Empress Alexandra Feodorovna and His Imperial Majesty the Sovereign Emperor, aid to the victims of the fire in the city of Tsaritsyn.

Russian source: Newspaper Starosti.

An immense forest fire has been burning for seven days in the district of Telavi (Georgia). Five towns are affected.

Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph has a yearly stipend of 45 million francs.

Czar Nicholas II of Russia receives 42 million francs annually. To that must be added annual proceeds of 100 million francs derived from his personal fortune. His yearly expenses are huge. The maintenance cost of his Imperial House alone drains 60 million francs. Moreover he spends 36 million francs on bonuses, salaries and gifts for his retinue of 32,000 stewards and servants whom he houses in palaces and castles sprawled across the empire.

King Alfonso XIII of Spain receives 9,400,000 francs annually.

| And Now For Something Completely Different |