The assassination of Pyotr Stolypin

Source: webpage and Lunapic

1. STOLYPIN AND THE REVOLUTION.

The assassination of the arch-hangman Stolypin occurred at a time when a number of symptoms indicated that the first period in the history of the Russian counter-revolution was coming to an end. That is why the event of September 1 (Old Style), quite insignificant in itself, again raises the extremely important question of the content and meaning of the counter-revolution in Russia.

One discerns notes of a really serious and principled attitude in the chorus of reactionaries obsequiously singing the praises of Stolypin, or rummaging through past intrigues of the Black-Hundred gang lording it over Russia, and in the chorus of the liberals who are shaking their heads over the "wild and insane" shot (it goes without saying that the former Social-Democrats of Dyelo Zhizni 1 who used that hackneyed phrase are found among the liberals).

Attempts are being made to regard "the Stolypin period" as a distinct chapter of Russian history.

Stolypin was the head of the counter-revolutionary government for about five years from 1906 to 1911. This was indeed a unique period crowded with instructive events. Outwardly it may be described as the period of preparing and staging the coup d'état of June 3, 1907.2 Preparation for this coup, whose consequences embrace all spheres of our social life, began in the summer of 1906 when Stolypin addressed the First Duma in his capacity as Minister of the Interior.

The question is: what social forces did the men who staged the coup rely upon or what forces prompted them? What was the social and economic content of the period ushered in on June 3?

Stolypin's personal "career" provides instructive material and interesting examples bearing on this question. A landowner and a Marshal of the Nobility,3 he was appointed governor in 1902 under Plehve, gained "fame" in the eyes of the tsar and the reactionary court clique by his brutal reprisals against the peasants and the cruel punishment he inflicted upon them (in Saratov Gubernia), organized Black-Hundred gangs and pogroms in 1905 (the Balashov pogrom4), became Minister of the Interior in 1906 and Chairman of the Council of Ministers after the dissolution of the First Duma. That is a very brief outline of Stolypin's political biography.

Stolypin's biography is also the biography of the class that carried out the counter-revolution. Stolypin was but an agent or clerk hired by this class. This class is the Russian landed nobility headed by Nicholas Romanov the first nobleman and biggest landowner. It is made up of thirty thousand feudal landlords who own seventy million dessiatines of land in European Russia—that is to say, as much land as ten million peasant households. Said latifundia undergird the extant feudal extortion which under various forms and names (labour-service, bondage, etc.) reigns in the traditionally Russian central provinces.

The "land hunger" of the Russian peasant (an expression coined by liberals and Narodniks) is but the obverse of the excess of land in the hands of this class. The agrarian question, mainstay of our 1905 Revolution, asked whether landed ownership would remain intact—in which case the poverty-stricken, wretched, starving, browbeaten and downtrodden peasantry would be the bulk of the population for many years to come—or whether the bulk of the population would gain for themselves a more or less human lifestyle with the civil liberties of European countries, a destiny attainable only through revolution.

[...]

The First Duma fully convinced the landowners (Romanov, Stolypin and Co.) that there could be no peace between them and the peasant and working-class masses. Their conviction fully accorded with objective reality. Deciding when or how the Duma election law should be changed—at once or gradually—was a minor detail.

The bourgeoisie wavered, showed that it feared the revolution a hundred times more than it feared reaction. That is why the landlords invited bourgeois leaders (Muromtsev, Heyden,5 Guchkov and Co.) to conferences where they explored the possibility of forming a joint Cabinet. And the entire bourgeoisie, including the Cadets, conferred with the tsar, the pogromists, the leaders of the Black Hundreds, about the means of combating the revolution whereas never once did the bourgeoisie send, since the end of 1905, a representative to confer with the leaders of revolution about how to overthrow the autocracy and the monarchy.

That is the main lesson to be drawn from the "Stolypin period" of Russian history. Tsarism consulted the bourgeoisie when the revolution seemed yet to be a force, but swung its jackboot to kick out all leaders of the bourgeoisie sequentially—first Muromtsev and Milyukov, then Heyden and Lvov, finally Guchkov—as revolutionary pressure from below slackened. The difference between the Milyukovs, Lvovs and Guchkovs is absolutely immaterial, merely a matter of correctly sequencing when these leaders turned their cheeks expecting the "kisses" of Romanov-Purishkevich-Stolypin and when they actually received them.

Stolypin left the scene at the very moment the Black-Hundred monarchy had extracted everything it could from the counter-revolutionary sentiments of the entire Russian bourgeoisie. Now that bourgeoisie—repudiated, humiliated and disgraced for having disowned democracy, the struggle of the masses and revolution—stands perplexed and bewildered, watching the symptoms of a new revolution gathering pace.

Stolypin helped the Russian people learn a useful lesson: either march under the leadership of the proletariat to freedom by overthrowing the tsarist monarchy or sink deeper into slavery under the ideological and political clout of the Milyukovs and Guchkovs, and submit to the Purishkeviches, Markovs and Tolmachovs.6

2. THE FAMINE AND THE REACTIONARY DUMA.

Not so long ago, under the influence of last year's harvest, the hack journalists confidently held forth on the beneficial results of "the new agrarian policy" and some naive persons took their cue and proclaimed that our agriculture had taken a turn and was improving throughout Russia.

Presently as if timed to coincide with the fifth anniversary of the decree of November 9, 1906,1 the famine and crop failure gripping nearly half of Russia have shown most graphically and incontrovertibly how much wanton lying or childish simplicity there was behind the hopes placed in Stolypin's agrarian policy.

Even according to official figures, whose honesty and "modesty" were displayed in previous famines, the present crop failure affects twenty gubernias. Twenty million people "are entitled to receive relief." In other words, they are bloated from hunger and their farms are ruined.

Kokovtsov would not be the Minister of Finance and the head of the counter-revolutionary government if he did not deliver "encouraging" remarks. There truly is no crop failure, you see, but merely "a poor harvest"; hunger "does not bring on diseases" but rather "sometimes cures" them; the tales about the suffering of the starving are all newspaper inventions, as governors eloquently testify; "the economic situation of the localities affected by the poor harvest is not so bad"; "the idea of handing out free food to the population is pernicious" and finally the measures adopted by the government are "sufficient and timely."

[...]

Hunger, typhus, scurvy, people eating carrion disputed with dogs or eating bread mingled with ash and manure. The "bread" was presented to the Third State Duma as evidence, but all these things do not exist for the Octobrists, to them the word of Kokovtsov the Minister of Finance is the law.

[...]

The feudal landlords on the Right have a "very simple" solution: the "loafing" muzhik must be made to work still harder and then "he'll deliver the goods." Markov the Second—that diehard from Kursk—deems it "horrible" that "out of 365 days in the year the muzhik works only 55-70 and does nothing the rest of the time" except warm his back on the stove and "demand a government ration."

3. FAMINE.

Again famine, as in the past, as in old pre-1905 Russia.

Crops may fail anywhere but only in Russia do they lead to such grave calamities, to the starvation of millions of peasants. The present disaster surpasses in extent the famine of 1891,1 as even supporters of the government and landlords are compelled to admit. Thirty million people have been reduced to the direst straits. Peasants are selling their allotments, their livestock, everything saleable, for next to nothing. They are selling their girls—a reversion to the worst days of slavery.

The national calamity reveals at a glance the true essence of our allegedly "civilized" society. Set in a different context and "civilization" our system is still the old slavery, the slavery of millions of toilers for the sake of the wealth and luxury of the "upper" ten thousand parasites. On the one hand there is hard labour—ever the lot of slaves—and on the other the absolute indifference of the rich to the slaves' fate. In past ages slaves were freely starved to death, women freely taken to their masters' seraglios, slaves tortured. In our day the peasants got robbed using all the tricks, accomplishments and progress of civilization—robbed to such an extent that they are starving, eating goosefoot, eating lumps of dirt in lieu of bread, suffering from scurvy and dying in agony. Meanwhile the Russian landlords, Nicholas II at their head, and the Russian capitalists are raking in money wholesale. The owners of amusement venues in the capital say that business has never been as brisk. Such barefaced unbridled luxury as is now flaunted in the big cities has not been seen for many years.

Why is it that of all countries it is in Russia alone that we still witness these medieval spells of famine side by side with modern progress?

Because Capital the new vampire preys upon Russian peasants bound hand and foot by feudal landlords, by the feudal landowning tsarist autocracy. Robbed by the landlord, crushed by the tyranny of officials, entangled in a web of police restrictions, harassed, persecuted and monitored by village policemen, priests and rural superintendents, the peasants are just as defenceless in the face of weather and capital as the African savages are. Nowadays it is only in savage countries where one finds cases of people dying from hunger in as huge numbers as they do in twentieth-century Russia.

But famine in present-day Russia is sure to teach the peasants a lot after hearing so many boastful speeches by the tsarist government on the benefits of the new agrarian policy, on the performance of farms that left the village commune, etc. The famine will erase millions of lives but it will also erase the last traces of the primitive slavish faith in the tsar which blinds peasants to the necessity of a revolutionary fight against the tsarist monarchy and the landlords.

The peasants can find a way out of their fate only by abolishing the landed estates. Only the overthrow of the tsarist monarchy—bulwark of the landlords—can bestow a life more or less worthy of human beings and deliverance from starvation and incurable poverty.

It is the duty of every class-conscious worker and every class-conscious peasant to make this clear. This is our main task in connection with the famine. Starting workingman collections of money for the starving peasants, wherever possible, and distributing such funds through the Social-Democratic members of the Duma is of course another requisite task.

4. THE PEASANTRY AND THE ELECTIONS TO THE FOURTH DUMA.

The tsarist government has already begun to "prepare" the elections to the Fourth Duma.1 Rural superintendents prodded by the circulars of the governors and the minister are trying to do their bit; the police and the Black Hundreds are showing their zeal; the "holy fathers" have been ordered to do their level best for the "Right" parties and are not letting the grass grow under their feet.

It is high time the peasants also began to think about the elections.

The elections are of particular importance to the peasants but their portion is very problematic. The peasants are the most scattered segment of the population, owing to the layout of agricultural production, and the least organized politically compared to both the workers and the liberal Cadet Party. Without political organization the peasants will be absolutely unable to offer resistance to the landlords and officials who are presently persecuting and mistreating them as never before. A group of Fourth Duma deputies really devoted to the cause of the peasantry, capable of defending its interests, politically conscious and organized, eager to broaden and strengthen the bond with the village peasants, could render an immense service to the union of all peasants in the struggle for freedom and life.

May such a group be formed in the Fourth Duma?

There were fourteen Trudoviks in the Third Duma who championed the democratic interests of the peasants. Unfortunately all too often they became dependent on the liberals—the Cadets—who are leading the peasants by the nose, deceiving them with the illusion of "peace" between peasants and landlords, between peasants and the landed tsarist monarchy. Withal it is a known fact that even the "Right" peasants of the Third Duma took a more democratic stand than the Cadets on the question of land. The agrarian bill introduced by forty-three peasant deputies of the Third Duma proves this incontrovertibly, and Purishkevich's recent "sally" against the Right peasant deputies shows that, in general, the Black Hundreds have every reason to be dissatisfied with them.

During the Third Duma the peasantry was taught the cruel lessons of the new agrarian policy, the "land misregulation" and the famine, that most terrible calamity. Thus its mood warrants the premise that it may certainly send democratic representatives to the Fourth Duma.

The main drawback is the electoral law! Framed by the landlords for their benefit and endorsed by the landlords' tsar it stipulates that the peasant deputies of the Duma shall be elected not by peasant electors but by the landlords, for the landlords can designate peasant electors of the peasant deputies who will go to the Duma! Obviously landlords will always pick peasants who follow the Black Hundreds.

Thus if peasants are to elect their own deputies to the Duma, if they are to elect truly reliable and staunch champions of their interests, they have only one possible course of action: to follow the example of the workers and choose exclusively electors who are Party members, class-conscious, reliable and thoroughly devoted to the peasantry.

The working-class Social-Democratic Party resolved in its last conference that already at meetings of the delegates (who elect the electors) workers must decide who will represent them in the Duma. All other electors must step down in their favour on pain of being boycotted and branded as traitors. Let peasants do likewise.

Preparation for the elections must be started at once. It is necessary to acquaint peasants with their circumstance and to create, wherever possible, even small village groups of politically-conscious peasants who will conduct the election campaign. At the meeting of their delegates, prior to selecting the electors, the peasants must decide who will represent them in the Duma; all other peasant electors must be requested to turn down, on pain of being boycotted and branded as traitors, any offers made to them by the landlords and categorically decline their nomination in favour of the candidate selected by the peasants.

All class-conscious workers, all Social-Democrats and all true democrats in general must lend the peasantry a helping hand in the elections to the Fourth Duma.

May the severe lessons of the famine and of the plunder of peasants' land not have been in vain.

May there be a stronger and more solid group of peasant deputies in the Fourth Duma, a group of real democrats loyal to the peasantry.

5. PYOTR STOLYPIN (Part I).

The Russian Government. The Czar of Russia has deposed Stolypin and given Kokovtsov the task of forming a new Government. The new Government will have an unequivocal leaning to the Right.

The entire Russian Government has submitted its resignation over difficulties arising from its project to create new municipalities [Zemstvos is the more appropriate term here, see April 5th item below, EFC].

The Czar did not want to accept Stolypin's resignation but at length did so and appointed Mr. Kokovtso, who leans further to the Right, as his substitute. Mr. Neratov remains provisionally in charge of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs during the illness of Sazonov the incumbent.

The Russian crisis. Russia's political situation gets more complicated each time owing to the creation of Zemstvos. The center of the Imperial Council wishes to interpellate Stolypin, but he will not consent to any interpellation until calm is restored.

St. Petersburg: On account of the recent assassination in Kiev of Stolypin the President of the Russian government several newspapers have published the following list of the more outstanding Russian personalities murdered by terrorists since 1904. Plehve the Minister of the Interior was murdered in St. Petersburgh on July 20, 1904. Grand Duke Sergei was murdered in Moscow on February 17, 1905. Bielostok's Police Prefect on March 7, 1905. Prince Nakashidze the Governor of Baku on May 24, 1905. Count "Suvalov" (?) the Moscow Prefect on May 24, 1905. General Sakharov the Governor of Saratov on December 7, 1905. Moscow's Police Prefect on December 27, 1905. General "Broganovitch" (?) the Vice Governor of Tambov on January 1, 1906. General "Dragomirov" (?) the Irkustk Police Prefect on January 11, 1906. "Steptzov" (?) the Governor of Tver on April 7, 1906. General "Zholtanovski" (?) the Governor of Elizabetgrad on May 6, 1906. Count Ignatyev the Governor-General on May 8, 1906. The victims of terrorist assassination since Ignatyev have been "very numerous" but none an eminent personality.

Kiev: At 10:00 PM on September 18 died Mr. Stolypin the President of the Council of Ministers gravely wounded on the 14th by Dmitry Bogrov at Kiev's Theater of the Opera. Many lawyers of St. Petersburgh College the terrorist's alma mater were arrested. Bogrov's family was imprisoned. Bagrov himself is seriously ill from the blows he received after his arrest.

Kiev: An immense crowd attended Mr. Stolypin's funeral. The cortege consisted of several Ministers, commissions from the Duma and the Imperial Council, top dignitaries of the Palace and other authorities. Some two hundred wreaths were deposited on the casket. The Metropolitan Archbishop of Kiev celebrated the funeral in the Cathedral. Troops fired three salvoes at the moment of the interment. Many people lingered at the door of the crypt praying for the soul of the dead man. The lawyer and policeman Dmitry Bogrov, the man who killed Stolypin, was executed on the 25th.1

STOLYPIN. He used to say, "Every morning when I get up and say my prayers I assume it to be my last day alive and I set out to do my duty with my sight fixed on eternity. When I return to my room at night I thank God for having granted me one more day alive." Stolypin was a great bureaucrat: admirable for his devotion to work, his personal honour, his modesty in dealing with people, his ability to overcome difficulties, his political talent. His true legacy is his repression of the revolutionaries. He imprisoned 100,000 conspirators, sent 20,000 rebels to Siberia, shot 5,000. The revolution deemed itself vanquished and the Czar was able to go once more to a public theater. When Pyotr Stolypin received his fatal wound he stretched out his hand to the royal balcony and blessed it with the sign of the cross; the auditorium too crossed themselves and the Russian national anthem sounded six consecutive times, everyone kneeling. That night there was talk in Russia of restarting pogroms.

6. PYOTR STOLYPIN (Part II).

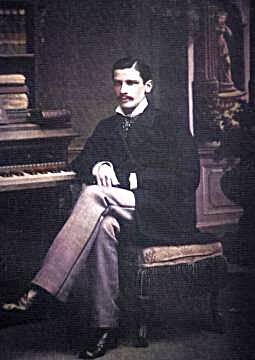

Pyotr Stolypin is one of the most prominent Russian statesmen of the reign of Emperor Nicholas II . His contemporaries and historians have mixed opinions about his personality: for some he is a cruel requiter and a reactionary, for others a great reformer and a patriot. Lenta.ru tells about the life and fate of Pyotr Stolypin.

Pyotr Arkadyevich Stolypin was born on April 14, 1862, in the German city of Dresden. His mother was a princess, his father a general in the artillery corps.

Pyotr Stolypin enrolled in the undergraduate program of the Natural Sciences Department in the Faculty of Physics and Mathematics at St. Petersburg Imperial University.

One of the lecturing professors at the University was Dmitry Mendeleev the famous chemist who gave Stolypin an A+ in Chemistry.

Stolypin graduated from St. Petersburg Imperial University in 1885 with a degree in Agronomy.

While still a 22-year-old undergraduate in 1884 he married Olga Neigard (1859-1944). She was the maid of honor of Empress Maria Feodorovna the mother of Nicholas II.

The marriage was a happy one: the couple supported and loved each other their entire lives. They had five daughters and one son: Maria (1885-1985), Natalia (1891-1949), Elena (1893-1985), Olga (1895-1920), Alexandra (1897-1987) and Arkady (1903-1990).

Stolypin started working for the Ministry of Internal Affairs in 1884.

In 1886 he was transferred to the Department of Agriculture and Rural Industry in the Ministry of State Property.

The young official climbed the ladder quickly. He was a leader of the Kovno district nobility in 1889-1898,1 honorary justice of the peace in 1890 and head of the entire Kovno nobility in 1898-1902. In his posts Stolypin paid special attention to the practical and legal aspects of Russian agriculture and to educating the peasants.

In 1903 Stolypin was appointed governor of Saratov province. He proved to be a dynamic administrator bent on improving the lot of the common people through administrative channels.

Stolypin restored law and order energetically after the populace of Samara province rampaged. He demonstrated rare courage venturing without protection into the middle of an angry crowd and calmly addressing the protesters to stifle their wrath.

Troublemakers would take potshots at him from bushes or hurl missives threatening to poison his two-year-old son. Confronted with his wife's fears, he would say: "I will continue my work. May the will of the Lord be fulfilled!"

On May 9, 1906, Nicholas II appointed Stolypin head of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. As Minister of Internal Affairs he supervised the police, gendarmerie, firefighting departments, Post and Telegraph, health services, press censorship, subsidiary administrations, food aid during crop failures, veterinary services, local courts, Zemstvos, non-Orthodox confessions and a number of additional duties. The position not only entailed great responsibility but also great danger. In 1902 Dmitry Sipyagin the former Minister of Internal Affairs had been shot dead at point-blank range and in 1904 his substitute, Vyacheslav Plehve, was blown up by a bomb.

On July 21, 1906, Stolypin was given the additional responsibility of Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Russian Empire. From his first days as Chairman of the Council of Ministers he began to modernize the country initiating a number of important reforms. He twice submitted his resignation (1909, 1911) but both times the Czar rejected it, he simply could not find a more active head of government.

In response to rampant revolutionary terror his provisional "Law on Military Field Courts" came into effect on September 1, 1906, and was enforced until April 1907 across eighty-two provinces; six hundred and eighty-three people were shot or hanged in Russia by the verdicts of military field courts.

Stolypin explained in a letter to governors-general, governors and city mayors,

The continuous agrarian unrest and armed revolts have ceased. These circumstances buttress the conviction that it will no longer be necessary to prolong the widespread use of military field courts.

Cadet deputy Fyodor Rodichev dubbed those military courts, "Stolypin's necktie." During a session break the offended Prime Minister challenged Rodichev to a duel. A frightened Rodichev rushed to Stolypin and apologized in the presence of several deputies. Stolypin forgave him but never again shook the Cadet's hand.

The Prime Minister's relations with the Duma failed to gel from the very beginning. The First State Duma turned out to be two-thirds in control of the leftists who instead of agrarian reform proposed confiscating the land of the landlords outright, nationalizing all the natural resources and abolishing private property altogether.

Speaking at the Duma, Stolypin pronounced these words that became famous:

The opponents of statehood would like to choose the path of radicalism, the path of liberation from Russia's historical past, of liberation from cultural traditions. They need great upheavals. We need a great Russia!

His relations with right-wing Duma parties were also difficult. These censured his bill on the creation of Zemstvos in the western provinces. Said bill pretended to sharply reduce the administrative weight of large landowners (mainly Poles) in favour of the small ones (Russians, Ukrainians and Byelorussians). However the bill was rejected by a majority vote of the Third State Duma in March 1911. Similarly a proposal to abolish the Pale of Settlement with the objective of discouraging disenfranchised young Jews from going over to the side of the revolutionaries was rejected by both the Duma and the Emperor.

Stolypin’s policies irritated the Right. The Left positively hated him.

The agrarian reform was his most important contribution: peasants were given equal rights with other classes, they were given freedom of movement and freedom to choose their own place of residence, the opportunity to study at universities and enter civil or clerical service without requiring the prior approval of the village commune or other authorities. Deputies from rural societies began to be elected by the peasants directly without prior assent of the governors. Legal restrictions were lifted for Old Believers. Ploughmen became owners of their allotments and were entitled to purchase state lands. Those wishing to move to virgin territory—Siberia and the Far East—were accorded benefits and special wagons for carrying people, belongings and livestock. There land was donated to the peasant not as his own but on a permanent lease. Over 3.7 million peasants migrated eastward between 1906-1914, establishing over ten thousand new villages and hamlets in Siberia and in the Far East.

In 1909 Austria-Hungary annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina and Europe sensed the outbreak of a major war between Germany and Russia. Stolypin managed to convince Nicholas II that military action would lead to revolution and consequently that a military conflict had to be averted at all costs.

Thereafter the Prime Minister assumed full control over the Ministry of Foreign Affairs formerly subordinated to the Emperor's will.

Stolypin survived ten assassination attempts. The most notorious one occurred on August 25, 1906, when terrorists detonated a powerful bomb concealed inside a horse-drawn carriage in front of the Prime Minister's official dacha on Aptekarsky Island of St. Petersburg. The high-pressure wave from the blast catapulted three-year-old Arkady and his older sister Natalya upward out of the front balcony and downward onto the pavement below. The boy suffered a broken hip and the girl had her legs maimed by the trampling of the panicked horses.

The eleventh assassination attempt proved fatal. On September 14, 1911, Stolypin was wounded at the Kiev Drama Theater by a 24-year-old double agent named Dmitry Bogrov who fired two shots nearly at point-blank range.

On September 18, 1911, at 9:53 PM, Stolypin passed away.

Many of Stolypin's reforms were left unfinished, others were assessed years later. A German governmental commission headed by the economics professor Otto Auhagen toured Russia to conduct covert reconnaissance on the eve of the First World War and concluded that had Stolypin's agrarian reform been consummated no one would be able to wage war against the Russians.

Stolypin said more than once that Russia required twenty years of internal and external peace—no wars or revolutions—for his reforms to be fully implemented. History denied him that wish.2

7. FROM RUSSIA.

For some days now a certain individual had been wandering over some Russian provinces claiming to be Tolstoy risen from the grave. Police apprehended and jailed him.

St. Petersburg: A Right deputy of the Duma questioned the Interior Minister in regard to the ritual assassination of a Christian child in Kiev ("it has been a ritual since the end of the first century of the Christian era and is still being practiced in some places"). The crime took place in March 1911 and the perpetrators were a band of Russian Jews. The deputy asked whether the criminals had been arrested and what their punishment had been. The murdered child was named Yushchinski. The Duma representative stated that if such crimes were repeated and not vigorously and immediately punished then the Russian people, in a legitimate use of their right to self-defence, should launch a general slaughter of the Jews.

St. Petersburg: Reports from various governments speak of big fires in several localities, the most important being those of "Chumicha" (?) and "Karanlovska" (?). Chumicha's blaze started at an oil terminal. The fire then spread to the commercial quarter consisting of more than forty buildings and acquired colossal dimensions. Losses are estimated to round three million rubles. The Karanlovska blaze was even more formidable. It started inside a grain silo. Flying sparks were carried by the wind to the cattle sheds, storehouses and a neighbourhood of three hundred wooden houses. The fire hydrants failed and everything burned down, consuming the wealth of many families. A thousand five hundred people lost everything and are forced to camp outdoors. Their misery is frightful.

Odessa: Ten thousand stevedores went on strike. The railwaymen want to follow suit. There is considerable apprehension that the strike may spread to every Russian port.

St. Petersburg: The stevedore strike has spread from Odessa to Riga to St. Petersburgh and to the ports on the Volga River. All reports state that the revolutionaries pretend to start a new uprising with the aid of secret Societies found all over Russia despite the police persecution. The twenty thousand stevedores on the River Neva belong to them. Powerful federations of labour unions operate underground in Moscow, Riga and Odessa. Many thousands of railwaymen belong to them.

Russian secret police operating abroad in Paris, London, Amsterdam, Berlin, Geneva, Liverpool, Hamburg and other cities have warned the government that many hundreds of revolutionaries have vanished from the local scene, presumably on their way to enter Russia illegally.

Many political prisoners have staged jailbreaks.

There is great agitation among students especially at the Medical School whose undergraduates wander over the poor neighbourhoods of St. Petersburgh every day. Under the pretext of delivering free medical advice they instead hold mysterious chats with riffraff who then vanish from the locality.

Numerous terrorist attempts evince the arrival of political emigrès to Russia. Top bureaucrats and some police chiefs have been assassinated in mysterious circumstances. The government undertakes great precautions and promises a tough response. There is a state of great alarm.

It's official, the works of Leo Tolstoy have been proscribed in the public libraries of Russia.

The Russian government has sent a note to the Ottoman Empire requesting the right of the Black Sea Fleet to cross the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles.

Persia has sent an ultimatum to Russia to remove its troops from Persian territory or face war.

Turkey denies Russia the right of passage through the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles.

New York: The U.S. Congress has approved a motion to abolish the trade treaty of 1832 between the U.S. and Russia. The reason is Russia's discrimination against Jews holding American passports. Russia deems them anarchists, nihilists and revolutionaries. The House bill has been forwarded to the Senate.

The U.S. Congress and the Senate have denounced the 1832 trade treaty with Russia.

St. Petersburg: Poverty and starvation are on the rise; the government has sent aid to the worst affected regions.

St. Petersburg: Horribly cold weather covers most gubernias. On February 22 at 11:30 PM the temperature in St. Petersburgh dropped to -30º C. Yesterday police patrols toured the poor neighbourhoods at dawn and took numerous persons with frozen feet and hands to hospitals. Many amputations were performed to avert gangrene. Police patrols found four men, a woman and two children frozen to death. City Hall has decreed that huge braziers be ignited outdoors shortly after 8:00 PM.

The Black Sea Fleet has been sighted near the mouth of the Dardanelles.

| And Now For Something Completely Different |