1. PURGING THE PARTY.1

The purging of the Party has obviously become a serious and vastly important affair.

In some places the Party is being purged mainly with the aid of the experience and suggestions of non-Party workers; these suggestions and those of the representatives of non-Party proletarian masses are heeded with due consideration. That's the most valuable and most important feature. If we purge our Party this way from top to bottom, without exceptions, it will be an enormous achievement indeed for the revolution.

[...]

Naturally we shall not heed everything the masses say. Sometimes they too vent regressive feelings particularly at times of exceptional weariness and exhaustion resulting from excessive hardship and suffering. But extremely valuable are in many cases their suggestions and their aversion to individuals who "cleave" to us for selfish motives or behave like "puffed-up commissars" or "bureaucrats".

The working masses who earn their bread by the sweat of their brow, who enjoy no privileges and have no "pull", have a fine intuition for distinguishing the honest and devoted Communists from the froth.2

Combing out ex-Mensheviks is a specific objective of the Party purge I would point to. In my opinion, not more than one hundredth of the Mensheviks who joined the Party after the start of 1918 should be allowed to stay, and even then, every one of these must be tested over and over again. Why? Because the Mensheviks displayed in 1918-21 the two qualities that characterize them as a trend: first, the adaptive skill to "adhere" themselves to prevailing trends among the workers, and second, the ability to even more deftly serve the whiteguards heart and soul with deeds while disavowing them with words.3

[...]

The Party must be purged of rascals, bureaucratic dishonest or wavering Communists and Mensheviks who powder their "façade" but stay Mensheviks at heart.4

I recently read an item by Okunev in Komsomolskaya Pravda about "carefree" theft. There was, it seems, a foppish young fellow with a moustache who carried on his "carefree" theft at one of our institutions. He stole systematically, incessantly, always without mishap. The noteworthy thing is not the thief as much as the fact that people around him who knew that he was a thief not only did nothing to stop him but, on the contrary, tended to pat him on the back and praise his dexterity. So the thief became something of a hero in the eyes of the public. That's what deserves attention, comrades, and it's the most dangerous thing of all.

When a spy or a traitor is caught, there are no bounds to the indignation of the public demanding that he be shot. But when a thief operates in the sight of everyone and steals state property, the people around him just smile good-naturedly and pat him on the back. Yet it's obvious that a thief who steals the people's wealth and undermines the interests of the national economy is no better, if not worse, than a spy or a traitor.

Finally, of course, this fellow, the fop with the moustache, was arrested. But what does the arrest of one "carefree" thief entail? There are hundreds and thousands of them. You cannot get rid of them all with the help of the G.P.U. Another measure, a more important and effective one, is needed here. It consists in creating around such petty thieves an atmosphere of moral ostracism and public detestation.

(J. V. Stalin. Works, 8, in The Economic Situation of the Soviet Union and Party policy, p. 143)

2. FOURTH ANNIVERSARY OF THE OCTOBER REVOLUTION.

[...]

Take religion or the denial of rights to women or the oppression and inequality of the non-Russian nationalities. These are all problems of the bourgeois-democratic revolution. The vulgar petty-bourgeois democrats discussed them for eight months.

In not a single one of the most advanced countries of the world have these questions been completely settled along bourgeois-democratic lines. They were settled completely by the legislation of the October Revolution in our country.

We have fought and are fighting religion in earnest.1 We have granted all the non-Russian nationalities their own republics or autonomous regions. We no longer have in Russia the base, mean and infamous denial of rights to women or sex inequality, that disgusting survival of feudalism and medievalism that is being renovated by the avaricious bourgeoisie and the dull-witted and frightened petty bourgeoisie of every other country in the world without exception.

[...]

Gentlemen, capitalists of all countries, keep up your hypocritical pretence of "defending the fatherland"; the Japanese fatherland against the American, the American against the Japanese, the French against the British, and so forth! Gentlemen, knights of the Second and Two-and-a-Half Internationals, pacifist petty bourgeoisie and philistines the world over, go on "evading" the question of how to combat imperialist wars and issue new "Basle Manifestos" (on the model of the Basle Manifesto of 1912).2 The first Bolshevik revolution has wrested the first hundred million people of planet Earth free from the clutches of imperialist war and of the imperialist world. Subsequent revolutions will deliver the rest of mankind from such wars and from such a world.

[...]

And we who during these three or four years have learned something about making sudden policy shifts—when these were required—have begun to learn how to shift to a new economic milieu (namely, to the New Economic Policy) zealously, attentively and sedulously, though not yet zealously, attentively and sedulously enough. We have begun making the necessary modifications to our economic policy and have already garnered some successes to our credit. Small and partial, true, but successes nevertheless.

The proletarian state must become a cautious, assiduous and shrewd "businessman"; a punctilious wholesale merchant. Otherwise it will never put this small-peasant country on its feet economically. In our current context of living side by side with a capitalist West—capitalist for the time being—no other route exists for moving forward to communism.

A wholesale merchant would appear to be an economic archtype as remote from communism as heaven is from earth. Withal it is one of the contradictions which, in real life, push a small-peasant economy via state capitalism toward socialism. The personal profit incentive will step up production (we must first and foremost increase production at all costs). The wholesale trade will bond the millions of participating small peasants and induce them to take the next step, namely, to form associations and cooperatives dedicated to production.

In this new "tuition" school we are already finishing the preparatory class. By persistent assiduous study, by making practical experience the test of every step we take, by not fearing to change over and over again what we have already started, by correcting our mistakes and most carefully analyzing their lessons, we shall graduate to a higher-level curriculum and take the whole "course" despite the present state of world economics and world politics which makes the course much longer and a lot harder than we would have liked.

No matter the cost, no matter how severe the hardships of the transition period may be, despite disaster, famine and ruin, we shall not flinch; we shall carry our cause triumphantly to its destination.

3. THE NEW ECONOMIC POLICY AND THE TASKS OF THE POLITICAL EDUCATION DEPARTMENTS.1

Comrades, I intend to devote this report (or rather talk) to the New Economic Policy and to the tasks (as I understand them) that arise out of this policy for the Political Education Departments. I think it would be quite wrong to exclude questions normally reserved for a congress from my report, to limit my report to bland information about the Party or the Soviet Republic.

[...]

At the start of 1918 we expected a protracted spell of peaceful construction. When the Brest[-Litovsk] peace was signed it seemed that the danger had subsided and that it would be possible to begin peaceful construction. But we were mistaken because in 1918 a real military danger surfaced in the shape of the Czechoslovak mutiny and the outbreak of civil war, which dragged on until 1920.

Partly owing to the overwhelming problems caused by the war and partly owing to the Republic's desperate plight when the imperialist war ended, owing to these circumstances and to a number of others, we made a wrong decision to go straightaway to communist production and distribution. We thought that under the surplus-food appropriation system the peasants would provide us with the quantity of grain allotted for distribution in the factories and thus set in motion communist production and distribution.

[...]

The countryside's surplus-food appropriation policy—a direct communist solution to the problem of urban development—hindered the growth of productive forces and was the main cause of the profound economic and political crisis we experienced in the spring of 1921.

That was why we had to take a step back. From the perspective of our initial policy it cannot be called other than a very severe defeat and retreat. Moreover it cannot be argued that this is a fully orderly retreat to previously set positions, as Red Army retreats were.

[...]

We say that every important branch of the economy must stand on the principle of personal incentive. There must be collective discussion but individual responsibility. When the people found themselves under new economic conditions they began immediately to discuss what would come of it and how the economy ought to be reorganized. We could not have started anything without this general discussion because the people had for decades and centuries been prohibited from discussing anything, and the revolution could not advance without the people everywhere holding meetings to argue about all matters for a certain length of time.

At every turn we suffer from our inability to apply this principle. The New Economic Policy demands that the areas of responsibility be drawn with absolutely sharp boundaries. This has created a lot of confusion. What happened was inevitable but harmless, it must be said. If we learn in good time to demarcate what is appropriate for meetings and what is appropriate for administration we will raise the welfare of the Soviet Republic to a proper level. Unfortunately we have not yet learned to do this. Most congresses are not business-like conclaves.

We surpass all other countries of the world in the number of congresses. Not a single democratic republic holds as many congresses as we do; nor could they allow it. We must remember that ours is a country that has endured great loss and impoverishment and we must teach it to hold meetings without mingling what is appropriate for meetings, as I have said, with what is appropriate for administration.

Hold meetings but govern without the slightest hesitation; govern with a firmer hand than the capitalist's who preceded you. If you do not, you will not vanquish him. You must remember that governance must be much stricter and a lot firmer than it was aforetime. The discipline of the Red Army was not inferior after many months of meetings to the discipline of the old army. Strict stern measures were adopted which include the death penalty, measures that even the former government did not apply. Philistines wrote and howled, "The Bolsheviks have introduced capital punishment." Our reply is, "Yes, we have introduced it and have done so deliberately." Whoever forgoes order and discipline now is letting the enemy infiltrate our midst.

We must say: either those who wanted to crush us (and who we think ought to be destroyed) perish, in which case our Soviet Republic will survive, or the capitalists survive and the Republic perishes.

We must say: you worked in the past for the benefit of the capitalists, the exploiters, and of course you did not do your best. We had deserters from the Army and also from the labour front. But now you are working for yourselves, for the workers' and peasants' state. Either those who cannot stand the pace in an impoverished country perish or the workers' and peasants' Republic will. There is no other choice or any room for sentimentality. Sentimentality is no less a crime than cowardice in wartime.

That's why I say that the New Economic Policy has an educational side to it too. Here you are discussing educational methods. You must go as far as to say that we have no room for the semi-educated. Educational methods will be milder when the communist stage is reached. But I say that presently education must be harsh. Otherwise we will perish.

Remember that the question at issue is whether we shall be able to work for ourselves. If we cannot, I repeat, our Republic will perish. And we say—as we said in the Army—that either those who want to cause our destruction perish or we must adopt the sternest disciplinary measures to save our country. Then our Republic will live. That's our line. That's why, among other reasons, we need the New Economic Policy.

Get down to business, all of you! You will have capitalists beside you, including foreigners, concessionaires and leaseholders. They will squeeze profits out of you to the tune of hundreds per cent. They will enrich themselves working beside you. Let them. Meanwhile you learn from them how to run the economy, and only when you have learned that, will you be able to build a communist republic. Since we must necessarily learn quickly, any slackness in this respect is a serious crime. And we must undergo this severe stern and sometimes cruel training because we have no other way out.

[...]

At one time we needed declarations, statements, manifestos and decrees. We've had enough of them.

At one time we needed them to show people how and what we wanted to build, what new and hitherto unseen things we were striving for. But can we go on showing people what we want to build? No. Even an ordinary labourer will begin to sneer at us and say: "What good is it to keep showing us what you want to build? Show us that you can build. If you can't build, we're not with you, and you can go to hell!" And he will be right.

[...]

What talk can there be of some new policy? God grant that we manage to stick to the old one if we have to resort to extraordinary measures to abolish illiteracy! That is obvious. But it's still more obvious that we performed miracles in the military and other fields.

The greatest miracle of all, in my opinion, would be if the Commission for the Abolition of Illiteracy were completely abolished, and if there were no proposals tabled for moving it out of the People's Commissariat of Education. Such prattle have I heard here. If it's true, and if you give it some thought, you will agree with me that an Extraordinary Commission should be created to abolish certain bad proposals.

More than that. It's not enough to abolish illiteracy, it's necessary to build up the Soviet economy and to that end literacy alone will not carry us very far. We must raise the republic's culture to a much higher level.

A man must make use of his ability to read and write. He must have something to read, newspapers, propaganda pamphlets. These should circulate smoothly and reach their destination without getting lost in transit, as they do now, so that no more than half are read and the rest are used in offices for some purpose or other. Perhaps not even a fourth reaches the people. We must learn to make full use of our scanty resources.

That's why we must ceaselessly propagate the idea, in association with the New Economic Policy, that political education calls for raising the cultural level at all costs. The ability to read and write must lift the cultural level, so peasants can improve their farms and their standard of living.

Soviet laws are very good laws because they give everyone the opportunity to combat bureaucracy and red tape, an opportunity that the workers and peasants of any capitalist state lack.2

But has anyone taken advantage of this? Hardly anybody! The peasants and a huge percentage of Communists do not know how to use the Soviet laws to combat red tape, bureaucracy, or such a truly Russian habit as bribery.

No less than half our Communists cannot combat bureaucracy, red tape or bribery, to say nothing of those who actually obstruct the fight. Ninety-nine per cent of you are Communists; you know that we are taking action against these obstructors. The Commission for Purging the Party is responsible for the operation and we hope to expel one to two hundred-thousand or thereabouts from our Party. Some say two hundred-thousand, and I rather like that figure. I very much hope we shall expel between one to two hundred-thousand members who glued themselves to the Party, who not only cannot fight red tape and bribery but even hamper the struggle. If we purge the Party of a couple of hundred thousand it will be useful, but that's only a tiny fraction of what we must do.

What hinders the fight? Our laws? Our propaganda? On the contrary! We have any number of laws! Why then don't we have success in this struggle? Because it cannot be waged solely with propaganda; the masses must cooperate.

Illiteracy must be combated. The Political Education Departments must tailor all their activities to this purpose, but literacy alone is likewise not enough. We also need culture that teaches us to fight red tape and bribery. It is an ulcer which, by the very nature of things, no military campaign or political reform can beat, only a higher cultural level can. That's a task that devolves upon the Political Education Departments.

Political teachers must not view their job as a bureaucratic one. This is the impression left by the discussions on whether Gubernia Political Education Department representatives ought to be appointed to Gubernia Economic Conferences.3

Excuse me for saying so, but I do not think that you should get appointed to any office; you should do your job as ordinary citizens. When you are appointed to some office you become bureaucrats; but if you deal with people and enlighten them politically, experience will show you that no bribery exists in a politically enlightened population.

At present bribery surrounds us on all sides. You will be asked what must be done to end it, to prevent so-and-so on the Executive Committee from taking bribes. You will be asked to show them how to curtail it; and if a political teacher replies that this is not his business or that pamphlets were published and proclamations were made on the subject, the people will style him a bad Party member. True, this lies outside the sphere of your department, we have the Workers' and Peasants' Inspection for that. But are you not members of the Party? You have taken the title of political teachers. When you were about to take it you were warned not to choose such a pretentious title, to choose some other more modest. But you wanted the title of political teachers and that implies a great deal. You did not take the title of general teachers but of political teachers. You may be told, "It's a good thing that you are teaching the people to read and write and to do economic campaigns, that's all very well, but it's not political education because political education is the sum total of everything."

We are doing propaganda against barbarism and against ulcers like bribery, and I hope you are doing the same, but political education is much more than propaganda. It expects tangible results. It means teaching the people how to obtain those results and setting an example for others, not as members of an Executive Committee but as ordinary citizens who are politically better educated and who can not only hurl imprecations at red tape (a very widespread habit amongst us) but also demonstrate how this evil can be overcome in practice. This is a very difficult art, not doable until the general level of culture is raised, until the mass of workers and peasants is more cultured than it is presently. I should most of all like to draw the attention of the Central Political Education Department to that task.

Now I would like to sum up my talk and suggest practical solutions to the problems facing Gubernia Political Education Departments.

In my opinion three chief enemies stand out; three tasks confront every political teacher who is a Communist, as most political teachers are. The three main enemies are: communist conceit, illiteracy and bribery.

A member of the Communist Party (not yet combed out) who fancies that he can solve all his problems by issuing communist decrees is guilty of communist conceit. Because he's still a member of the ruling party employed in some government office, he imagines being entitled to talk about the results of political education. Nothing of the sort! That's only communist conceit. The point is to learn how to impart political knowledge. We have not yet learned how to tackle the subject adequately.

As regards the second enemy, illiteracy, I can say that as long as it exists in our country, to talk about political education is over the top. Literacy is not a political problem but a boon without which any talk about politics is useless. An illiterate person stands outside politics, he must first learn his ABC. Without it there are only rumours, gossip, fairy tales and prejudices, not politics.

Lastly, if bribery exists it is useless to talk about politics. Here we do not even have an approximation to politics; here it's impossible to do politics because all measures are left hanging in the air and yield absolutely no results. The application of a law where bribery is rampant only makes matters worse. Under those conditions no politics whatever can be pursued; the fundamental basis for engaging in politics is missing.

We must absorb that the masses need to have a higher cultural level before we can outline our political tasks to them or tell them what they must strive for (this is what we should be doing!). We must transmit this higher level. Otherwise it will be impossible to really solve our problems.

A cultural problem cannot be solved as quickly as a political or military problem. It must be understood that the conditions for progress are no longer what they were. In a period of acute crisis it's possible to get a political victory in a few weeks. It's possible to have victory in war in a few months. But it's impossible to obtain a cultural victory in so short a spell. By its very nature a cultural victory requires a longer span; and we must adapt ourselves to this, plan our work accordingly and display maximum perseverance, persistence and method. Without these qualities it is impossible to even begin the task of political education. And the only criterion for determining the results of political education is a measurable improvement in industry and agriculture.

We must not only abolish illiteracy and the bribery which sprouts on the soil of illiteracy but we must get the people to really accept our propaganda, our guidance and our pamphlets so that our national economy might improve.

Those are the functions of the Political Education Departments in connection with the New Economic Policy, and I hope that this Congress will help us achieve greater success in this field.

The Political Education Departments were formed by local public education bodies (volost, uyezd and gubernia) in conformity with the decree issued on February 23, 1920. Their work was guided by the Central Political Education Committee at the People's Commissariat of Education.

2 Soviet laws are very good laws because they give everyone the opportunity to combat bureaucracy and red tape - Six years later, on December 3, 1927, this is what Stalin reported to the Fifteenth Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union,I shall not dilate on those defects in our state apparatus that are glaring enough as it is. I have "Mother Red Tape" in mind primarily. I have at hand a heap of materials on the matter of red tape, exposing the criminal negligence of a number of judicial, administrative, insurance, co-operative and other organizations.

Here is a peasant who went to a certain insurance office twenty-one times to get some matter put right and even then failed to get any result.

Here is another peasant, an old man of sixty-six, who walked 600 versts [640 kilometers] to get his case cleared up at an Uyezd Social Maintenance Office and even then failed to get any result.

Here is a fifty-six-year-old peasant woman who in response to a summons by a People's Court walked 500 versts [533 kilometers] and travelled over 600 versts by horse and cart; and even then failed to get justice done.

A multitude of such facts could be quoted. It is not worthwhile enumerating them. But this is a disgrace to us, comrades! How can such outrageous things be tolerated?

(J. V. Stalin. Works, 10, in Political Report of the Central Committee, II §4, pp. 328-9)

4. REPORT OF THE CENTRAL EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE AND OF THE COUNCIL OF PEOPLE'S COMMISSARS, NINTH ALL-RUSSIA CONGRESS OF SOVIETS.1

(Stormy applause. Cries of "Hurrah!", "Long live our leader, Comrade Lenin!", "Long live the leader of the world proletariat, Comrade Lenin!" Prolonged applause).

Comrades, I have to make a report on the foreign and home situation of the Republic. This is the first time I am able to make such a report after a whole year has passed without any large-scale attack by Russian or foreign capitalists against our Soviet power. This is the first year that we have been able to enjoy a relative respite from attacks and been able to apply our energies in some degree to our chief and fundamental tasks, namely, the rehabilitation of our war-ravaged economy, the healing of the wounds inflicted on Russia by the exploiting classes that were in power before us, and the laying down of the foundations of socialist construction.

[...]

We made considerable progress in 1921 (the first year of trade with foreign countries). This was partly due to the improvement in our transportation network, perhaps the most important or one of the most important sectors of our economy. It is also due to our imports and exports. Permit me to quote very brief figures.

The burden and most crucial feature of all our most incredible difficulties lie in fuel and food, in the peasant economy, in the famine and in the calamities that have afflicted us. We know very well that all this is bound up with the transportation problem. We must discuss this, and all comrades from the localities must realize and repeat over and over again to all their comrades there that we must strain every nerve to overcome the food and fuel crisis. This is what our transportation system ails from, and transportation is the material tool for our relations with foreign countries.

The improvements in our transportation network over the past year are beyond doubt. In 1921 we transported by river much more than in 1920. The average run per vessel in 1921 was a thousand pood-versts as compared with eight hundred pood-versts in 1920.2 We have definitely made some progress.3

I must say that we are beginning to obtain assistance from abroad for the first time. We have ordered thousands of locomotives and we have already received the first thirteen from Sweden 4 and thirty-seven from Germany. It's a tiny start but a start nevertheless. We have ordered hundreds of tank cars; about five hundred arrived during the course of 1921.

We are paying a high exorbitant price for these items, withal it shows that we are receiving the assistance of the large-scale industry of the developed countries. It shows that the large-scale industry of capitalist countries is helping us restore our economy although all are governed by capitalists who hate us heart and soul, whose governments yet vacillate on a de jure recognition of Soviet Russia and still debate whether the Bolshevik Government is legitimate or not. Lengthy research uncovered that it is a legitimate government but cannot be recognized. I have no right to hide the sad truth that we are not yet recognized, but I must tell you that business deals are nonetheless being struck.

All these capitalist countries are in a position to make us pay through the nose, we pay more for their goods than they are worth, but for all that, they are helping our economy.

How did that happen? Why are they acting against their own inclinations and in contradiction with what their press constantly asserts? Their press is more than a match for ours in terms of circulation figures and in terms of the force and venom it spews. They call us criminals, and all the same help us.

And so it turns out that they are bound up with us economically. It turns out, as I have already said, that our calculations made on a grand scale are more accurate than theirs. This is not because they don't have people capable of making sound calculations (they have far more than us) but because it is impossible to calculate accurately when one is heading for destruction.5

[...]

5. POLITICAL REPORT OF THE CENTRAL COMMITTEE, ELEVENTH CONGRESS OF THE RUSSIAN COMMUNIST PARTY.1

[...]

Now, however, the position is that we must put our work to a serious test. [...] I am referring to a test of the whole economy.

The capitalist was able to supply things. He did it inefficiently, charged exorbitant prices, insulted and robbed us. Ordinary workers and peasants who don't argue about communism because they don't know what it is are well aware of this.

"But the capitalists were, after all, able to supply things—can you? No, you cannot." That's what we heard last spring albeit not always loud and clear. It was the undertone of the whole of last spring's crisis. "You are splendid people but you cannot cope with the economic task you embarked upon." This is the simple withering criticism which the peasantry, and through it some sections of the workers, levelled last year at the Communist Party. That's why this old dispute is so significant in the New Economic Policy environment.

We need a genuine test. The capitalists are working beside us; they hustle like thieves, they make a profit, but they know how to do things. "But you, you are trying out a new way, you make no profit and you don't know how to do things. Your principles are communist, your ideals splendid, they are laid out so beautifully you seem saints deserving a bodily rapture to heaven. But can you get things done?"

We need a test, a real test, not the kind the Central Control Commission makes when it censures somebody and the All-Russia Central Executive Committee imposes some penalty. Yes, we want a genuine test from a national economy perspective.

We Communists got many deferments and more credit than ever was granted a government. Of course we Communists helped to get rid of the capitalists and landowners. The peasants appreciate this and have alloted us extra time, longer credit, but only for a spell—after which comes the test: "Can you run the economy as well as the others? The old capitalist can; you cannot."

That's the first lesson, the first important part of the political report of the Central Committee. We cannot run the economy. This was proven this past year. I would very much like to quote several examples [...] to illustrate how we ran the economy. Unfortunately, for a number of reasons, largely owing to ill health, I was unable to elaborate this part of my report and so I must limit myself to expressing my conviction based on my observations of what is going on.

Over this past year we showed quite clearly that we could not run the economy. That's the fundamental lesson. Either we prove the opposite this coming year or Soviet power will not be able to persist.

The biggest danger is that not everyone realizes this. If all of us Communists (the responsible officials) see clearly that we lack the ability to run the economy, that we must learn how to from page one, we will win. That's the fundamental conclusion, in my opinion, to be drawn.

But many of us do not grasp this and believe that only the ignorant people who have not studied communism can say so; some day perhaps the ignorant will learn and understand.

No, excuse me, the point is not that the peasant or non-Party worker did not study communism. The point is that the time is up when the job was to draft a great programme and call upon the people to carry it out. That time is finished. Today you must prove that you can provide tangible assistance to the workers and peasants under the current difficult conditions and thus demonstrate to them that you have withstood the test of capitalist competition.

The mixed companies which we have started to create, where private Russian and foreign capitalists participate together with Communists, provide a means of learning how to construct a competitive economy properly and of showing that we can provision the peasant economy as well as the capitalists do, that we can meet the peasantry's demands, that even presently we can improve the peasant's lot in spite of his backwardness (for it's impossible to remold him quickly).

That's the sort of competition facing us, an absolutely urgent task. In my opinion it's the pivot of the New Economic Policy and the quintessence of the Party's policy. [...]

But here is something we must do in the economic sphere now. We must win the competition against the ordinary shop assistant, the ordinary capitalist, the merchant who will go to the peasant without arguing about communism. Just imagine, he will not argue about communism but will say: if you want to have some item or trade properly or build something, I'll do it for you at a high price, but the Communists may charge you ten times higher. This kind of agitation is now the crux of the matter; this is the root of economics.

[...]

We must ... not rest content with the fact that there are responsible and good Communists in all the state trusts and mixed companies. That's no good because these Communists do not know how to run the economy 2 and are inferior in that regard to ordinary capitalist salesmen trained in big factories and big firms. But we refuse to admit this. In this sphere communist conceit ... still persists.

The whole point is that responsible Communists, even the best ones, unquestionably honest and loyal, who in the old days suffered penal servitude and did not fear death, don't know how to trade because they are not businessmen, they have not learned the business, do not want to learn it and don't understand why they must study starting from page one.

Communists, revolutionaries who accomplished the greatest revolution on earth, whom the eyes of forty "pyramids" (i.e., forty European countries) turn to in the hope of emancipation from capitalism, must take lessons from ordinary salesmen! But these ordinary salesmen have ten years' experience in warehouses and know the business of shipping and handling well whereas the responsible Communists and devoted revolutionaries do not, and do not even admit it.

[...]

Now I come to the question of halting the retreat, a question I dealt with in my speech at the Congress of Metalworkers.3 Since then I have not heard any objections in the Party press, in private letters from comrades, or in the Central Committee.

The Central Committee approved my plan, which was, that strong emphasis should be laid on calling a halt to this retreat in the report of the Central Committee to the present Congress, and that accordingly the Congress should give binding instructions on behalf of the whole Party. For a year we have been retreating. This period is drawing or has drawn to a close. On behalf of the Party we must now call a halt. The goal of the retreat has been achieved. We now have a different objective, that of regrouping our forces. We stand on a new frontline.

On the whole we have conducted the retreat in fairly good order. True, not a few voices were heard from various sides which tried to convert this retreat into a stampede. For example, several members of the group which bore the name "Workers' Opposition" (I don't think they had any right to that name) argued that we were not retreating adequately in some sector or other. Owing to their excessive zeal they found themselves at the wrong door as they now realize. At that time they did not see that their activities did not help us correct our bearing but merely had the effect of spreading panic and hindering our effort to beat a disciplined retreat.

A retreat is a difficult matter especially for revolutionaries accustomed to advancing with enormous success for several years, and especially if they are surrounded by revolutionaries in other countries who are longing for the time when they can launch an offensive. Seeing that we were retreating, several burst into tears in a disgraceful and childish manner, as happened in the last extended Plenary Meeting of the Executive Committee of the Communist International. Moved by the best communist sentiments and communist aspirations, several comrades burst into tears because—oh horror!—the good Russian Communists were retreating. Perhaps it's now hard for me to understand this West-European mentality although I lived in those marvellous democratic countries for quite a number of years as an exile. Perhaps from their point of view this is such a difficult matter to understand that it's enough to make one weep. We at any rate have no time for sentiment.

It was clear to us that because we had advanced so successfully for so many years, had achieved so many extraordinary victories in a country without material resources that lay in an appalling state of ruin, and because the ground we had gained was so extensive it was absolutely essential to drop back and consolidate our advance. We could not retain all the ground captured in the first onslaught. On the other hand, because we had taken so much ground riding the crest of a wave of enthusiasm borne by workers and peasants, we now had enough distance to return to our frontline base safely.

Our pullback was on the whole fairly orderly although certain panic-stricken voices, among them the Workers' Opposition, provoked desertions in our ranks, incurred a relaxation of discipline and disturbed the orderly retreat (this was the tremendous harm done!).

The worst hazard in a pullback is panic. When a whole army gives ground (I speak figuratively) it does not have the morale of an advance. A certain mood of depression endues every step. We even had poets who wrote that people were cold and starving in Moscow, that "everything before was bright and beautiful but now trade and profiteering abound." We have had quite a number of poetic effusions of this sort.

Of course a fallback breeds all this and that's where its serious hazard lies. It is terribly difficult to retreat after a great victorious surge because the force relations are reversed. During a victorious advance everybody presses forward of his own accord even if discipline is relaxed. During a retreat, however, discipline must be more conscientious and becomes a hundred times more necessary because a receding army does not perceive when or where it should halt. It sees fallback only, and a few panic-stricken voices can trigger a stampede. The risk here is enormous. When an authentic army is retreating, machine-guns are kept ready to shoot, and when an orderly retreat degenerates into a disorderly flight, the command to fire is given, and quite rightly so.

If during an incredibly difficult fallback [the New Economic Policy] anyone spreads panic (even from the best of motives) when everything hinges on preserving a proper order, the slightest breach of discipline must be punished severely, sternly, ruthlessly;4 and this applies not only to certain internal Party affairs [the Workers' Opposition] but also and to a greater extent to such gentry as the Mensheviks and all of the Two-and-a-Half Internationals.

The other day I read in number twenty of The Communist International an article by Comrade Rakosi on a new book by Otto Bauer, from whom at one time we all learned but who, like Kautsky, became a miserable petty bourgeois after the war.5

Bauer now writes: "There, they are now retreating to capitalism! We always said that it was a bourgeois revolution." Indeed, the sermons which Otto Bauer, the leaders of the Second and Two-and-a-Half Internationals, the Mensheviks and the Socialist-Revolutionaries preach express their true nature. "The revolution has gone too far. What you are saying now is what we have been saying all along, permit us to say it again." But we say in reply: "Permit us to put you before a firing squad for saying that. Either you refrain from expressing your views or, if you insist on expressing your political views publicly in the present circumstances when our position is far more difficult than it was when the whiteguards were attacking us directly, you will have only yourselves to blame if we treat you as the worst and most pernicious whiteguard elements."

And the Mensheviks and the Socialist-Revolutionaries who all preach this sort of thing are astonished when we declare that we shall shoot people for such views. They are amazed, but surely it's obvious. When an army retreats, a hundred times more discipline is required than when it advances. If everybody started rushing back now, it would spell immediate and inevitable disaster.

The most important thing is to retreat in good order, to foreordain the precise limits of the pullback and to not give way to panic. And when a Menshevik says, "You are now retreating; I have been advocating retreat all the time, I agree with you, I am your man, let us retreat together," we reply, "For the public manifestation of Menshevism our revolutionary courts must pass the death sentence, otherwise they are not our courts, but God knows what." They cannot understand this and exclaim, "What dictatorial manners have these people!" They still think we are persecuting them because they fought us in Geneva.6 Were it so we would have been unable to hold power even for two months. We must never forget this.

[...]

The retreat is at an end. The principal layouts of working with the capitalists are outlined. We have examples, albeit an insignificant number [seventeen mixed companies].

Stop philosophizing and arguing about the New Economic Policy. Let poets write verses, that's what poets are for. But you economists, you stop arguing about the New Economic Policy and form more mixed companies. Find out how many Communists can compete with the capitalists. Look at things more soberly.

The pullback has come to an end; it's now time to regroup our forces. These are the instructions that the Congress must pass to put an end to fuss and bustle. Calm down, do not philosophize. If you do, it'll be counted against you. Show by tangible efforts that you can work no less efficiently than the capitalists.

The capitalists link economically with the peasants in order to amass wealth; you must link with the peasant economy in order to bolster the economic strength of our proletarian state. Your advantage over the capitalists is that political power rests in your hands; you have a number of economic weapons at hand. The only problem is that you cannot use them properly.

Cast off the tinsel and the festive communist attire, learn a simple thing simply and we shall beat the private capitalist. We possess political power; we possess a host of economic weapons. If we beat capitalism and create a link with peasant farming we shall become an absolutely invincible power. Then the building of socialism will not be the task of the Communist Party, that drop in the ocean, but the task of the entire mass of working people. Then rank-and-file peasants will see us helping them and follow our lead. Consequently even if the pace is a hundred times slower it will be a million times firmer and surer. It is in this sense that we must refer to the end of the pullback; and the proper thing to do is to make this slogan a Congress decision one way or another.

[...]

I should like to quote a passage from a pamphlet by Alexander Todorsky.7 It was published in Vesyegonsk (there is an uyezd town of that name in Tver Gubernia) on the first anniversary of the Soviet revolution in Russia (November 7, 1918), a long, long time ago. Evidently this Vesyegonsk comrade must be a member of the Party, I read the pamphlet a long time ago and cannot say for sure.

He describes how he set about equipping two Soviet factories. He enlisted the services of two bourgeois. He did this in the way these things were done then. He threatened to imprison them and confiscate all their property. We know how the services of the bourgeoisie were enlisted in 1918; so there is no need for me to go into details.

(Laughter)

The methods we are using now to enlist the bourgeoisie are different.

They were enlisted for the task of restoring the factories. But here is the conclusion he arrived at: "This is only half the job. It's not enough to defeat the bourgeoisie, to overpower them; they must be compelled to work for us."

Now these are remarkable words. They are remarkable for they show that even in the town of Vesyegonsk, even in 1918, there were people who had a correct understanding of the relationship between the victorious proletariat and the vanquished bourgeoisie.

It's only half the job when we rap the exploiters' knuckles, render them innocuous, overpower them.

In Moscow, however, ninety out of a hundred responsible officials imagine that all we have to do is overpower, render innocuous and rap knuckles. What I have said about the Mensheviks, the Socialist-Revolutionaries and the whiteguards is very often interpreted exclusively as overpowering, rendering innocuous and rapping knuckles (and perhaps some other spots). But that's only half the job. It was only half the job in 1918 when this was written by the Vesyegonsk comrade; now it's even less than a quarter of the job done.

We must make those hands work for us and not have responsible Communists at the head of departments, enjoying rank and title, but actually swimming downstream with the bourgeoisie. That's the whole point.

The idea of building a communist society exclusively with the hands of Communists is childish, absolutely childish.9

We Communists are but a drop in the ocean, a drop in the ocean of humanity.

We shall be able to lead the people along the path we have chosen only if we chart it correctly. From the perspective of the progression of world history we charted it correctly as the situation in every country shows. Now we must also chart it for our country. But the progression of world history is not the sole determining factor for us. Other factors are whether there will be another military intervention or not, and whether we shall be able to supply the peasants with goods in exchange for their grain. If we are not able, the peasants will say: "You are splendid fellows; you defended our country. That's why we obeyed you. But if you cannot run the show, get out!" Yes, that's what the peasants will say.

[...]

On arriving to Moscow at the end of February I heard bitter complaints, "We cannot buy the canned goods." There was a ship at Libau with a cargo of canned goods, and the owners were even prepared to take Soviet currency for real canned goods!

(Laughter)

If these canned goods are not entirely spoiled (and I emphasize the if now because I'm not sure whether I will ask for another investigation whose outcome we shall have to report on at the next Congress). If, I say, these goods were not entirely bad and had been purchased, I ask: why could this matter not have been settled without Kamenev and Krasin?

From the report I have before me I gather that one responsible Communist sent another responsible Communist to the devil. I also gather from this report that one responsible Communist said to another responsible Communist, "From now on I shall not talk to you except in the presence of a lawyer."

Reading this report I recalled the time when I was in exile in Siberia twenty-five years ago and had occasion to act in the capacity of a lawyer. I was not a certified lawyer because I was not allowed to practise, being summarily exiled, but as there was no other lawyer in the area, the people came and confided their troubles to me. But sometimes I had the greatest difficulty in grasping what the trouble was.

A woman would come and of course start telling me a long story about her relatives, and it was incredibly difficult to get from her what she really wanted. I said to her: "Bring me a copy." She went on with her endless and pointless story. When I repeated, "Bring me a copy," she left complaining, "He won't hear what I have to say unless I bring a copy." In our colony we had a hearty laugh over this copy.

I was able to make some progress however. People came to me, brought copies of the necessary documents and I was able to gather what their trouble was, what they complained about, what ailed them. This was twenty-five years ago in Siberia in a place many hundreds of versts away from the nearest railway station.

But why was it necessary in the capital of the Soviet Republic, three years after the revolution, to have two investigations, the intervention of Kamenev and Krasin and the instructions of the Political Bureau to purchase canned goods? What was lacking? Political power? No. The money was forthcoming, so they had economic as well as political power. All the necessary institutions were there. What was missing then? Culture. Ninety-nine out of every hundred officials of the M.C.C.S. 8 (against whom I have no complaint whatsoever and whom I regard as excellent Communists) and officials of the Commissariat of Foreign Trade lack culture. They were unable to approach the issue in a cultured manner.

When I first heard of the matter I sent the following memo to the Central Committee: "All officials involved from the Moscow government departments (excepting members of the All-Russia Central Executive Committee who, as you know, enjoy immunity) should be put in the worst prison of Moscow for six hours and those from the People's Commissariat of Foreign Trade for thirty-six."

And then it turned out that no one could identify the culprits...

(Laughter)

and from what I have told you it's evident the culprits will never be found out.

It's simply the usual inability of Russian intellectuals to get things done: inefficiency and slovenliness. First they rush at a job, do a little bit, ponder, and when nothing comes of it they run to complain to Kamenev and wish the matter brought before the Political Bureau.

[...]

We are living in the twentieth century and the only nation that emerged from a reactionary war by revolutionary methods, not for the benefit of a particular government but by overthrowing it, was the Russian nation; and it was the Russian revolution that extricated the nation.

What has been won by the Russian revolution is irrevocable. No power on earth can erase it; nor can any power on earth erase the fact that the Soviet state has been created. This is a historical victory. For hundreds of years states were built according to the bourgeois model, and for the first time a non-bourgeois form of the state has been unveiled.

Our machinery of government may be faulty, but it's said that the first steam engine was also faulty. No one even knows whether it worked or not, but that's not the important point; the important point is that the steam engine came into being. Even assuming that the first steam engine was useless the fact is that we now have and use them.

Even if our machinery of government is very faulty, the fact remains that it has been created. The greatest invention in history has been made: a proletarian type of state. Therefore let all Europe, let thousands of bourgeois newspapers spread news about the horrors and poverty that prevail in our country, about suffering being the sole lot of the working people in our country; the workers all over the world are still drawn towards the Soviet state. [...]

It must be admitted, and we must not be afraid to do so, that in ninety-nine out of a hundred cases the responsible Communists are not in the right jobs, they flounder in their duties and they must sit down to learn. If this fact is admitted—now that thanks to the broad international situation we will have ample time and chance to learn—we must learn, come what may.

(Stormy applause).

6. TELEGRAM TO THE WORKERS AND ENGINEERS OF THE AZNEFT TRUST.1

On the night of April 9 enemies of the working class tried to destroy the Surakhan oilfields at Baku by fire.

I have learned of instances of extraordinary heroism and courage displayed by the workers and engineers of the oilfields who contained the fire at tremendous risk to their own lives, and consider it my duty to thank the workers and engineers of the Surakhan oilfields on behalf of Soviet Russia.

These examples of heroism show better than anything else that despite all the difficulties and the continual conspiracies of the whiteguard Socialist-Revolutionary enemies of the workers' republic, the Soviet Republic will emerge triumphantly from all difficulties.

V. Ulyanov (Lenin)

Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars

In May 1920 Alexander Pavlovich Serebrovsky (photograph below, right) was appointed head of the Azneft Trust by a decision of the Council of People's Commissars of the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic. He was a Bolshevik who knew Lenin personally.

Serebrovsky had received initial technical education in Russia until 1917, had earned a mechanical engineering degree in Belgium and had worked in Russian and foreign factories.

He proposed to "Americanize" the oil industry by purchasing the latest American oil industry equipment and by concluding an agreement with Standard Oil and with the British Vickers Ltd. He assumed that the primary reason for the industrial leadership of the U.S.A. was technology and equipment. The Soviet economic leaders of the New Economic Policy period believed that by purchasing American technology and equipment they could reproduce in the U.S.S.R. the labour productivity of the United States. Additionally the "Red directors of industry" studied the management techniques covered in Western textbooks published in the 1920s and took notes from the memoirs of J.D. Rockefeller and E. Carnegie.

He travelled to Turkey in 1921 to make a first business contact with Henry Mason Day the president of the International Barnsdall Corporation and with its petroleum engineer Morris.

[The New York Times, July 14, 1957, page 73: "At one time Mr. Day was credited with holding Russian concessions worth many millions in oil, manganese, tobacco and flax. He was credited with authorship of a contract with the Russians for the development of the Baku oil field said to be the most extensive contract of its kind ever written"].

Subsequently Morris the petroleum engineer went to inspect the Baku oil field. As Serebrovsky recalled, Morris was "horrified" at seeing how things were done.

The American pointed out that it was reckless to work so rudimentarily, that oil wealth, gas, gasoline, etc. could not be wasted. He criticized the extraction of oil with bailers harshly. A modern oil industry, he stressed, must transition to modern drilling (rotary) machines and pumps.

"You are beggars sitting on gold and dying of hunger; I will teach you how to work!" he exclaimed.

The Azneft Trust needed urgent technical assistance indeed, so it signed a 15½-year contract with the International Barnsdall Corporation in September 1922 for the delivery of equipment and for the training of Soviet oil workers.

The Azneft Trust was to pay the American corporation 60,000 gold rubles per well drilled and to hand over 20% of the oil extracted from that well.

At the completion of the contract all the equipment installed by the International Barnsdall Corporation would devolve to the Azneft Trust.

On August 30, 1924, the Bolsheviks terminated the contract because they supposed that they had learned everything they needed to know from International Barnsdall Corporation.

Serebrovsky admired the precise well-managed work of the American oil companies, similar to the running of a well-tuned machine that hardly requires the services of a mechanic. But it proved impossible to fully reproduce the American model in a Soviet environment.

Serebrovsky highlighted a number of serious problems that the Azneft Trust had to overcome: shortcomings in state supplies, low Soviet product quality and high prices. Whereas machine shops and electrical equipment manufacturers in the United States supplied and constantly upgraded the items that the oil industry needed, the Soviet machine shops failed to heed their oil industry's needs. The dominance of distribution relationships, the absence of direct contact with the market, the fixed state prices, the regulations, the instructions on who to do business with and direct subordination to Moscow fettered the Soviet oil trusts, so they always tailed those of the United States where profitability was the sole benchmark of success.

Thus Serebrovsky tried to reproduce the principles of management used by the American oil companies in a Soviet environment, but the experiment failed because the Soviet oil industry was constrained by the quirks of the Soviet political system.

P. Chambers, an American consultant with twenty-seven years' experience was hired to solve a number of problems at Baku's Schmidt plant. He discovered technical spec violations galore plus the use of "pirated" copies of American tools and machines being rolled out by as many as ten different machine shops.

These "pirated" items broke down quickly, an outcome which terrified the workers who feared being accused of sabotage.

The Schmidt plant brushed off the American's recommendations and instructions, so Chalmers revoked his contract and went back to the States.

By 1925 the Azneft Trust had six oil production sites, six oil refineries, nine machine shops and modern facilities for storing the oil products.

A major social accomplishment of the Azneft Trust was its overhaul of the old dilapidated housing assigned to its workers. The trust built new American-standard wooden cottages (photograph below) and imported American household appliances never before seen in the region: gas stoves, washing machines, vacuum cleaners, etc.

In 1937 the journal "Oil Industry" noted that the average lifespan of wells in the U.S.S.R. was stuck at the pre-revolutionary level of 5 years. Five years was also the average lifespan of a well in the United States away back in the 1870s when oil was extracted with primitive methods.

As of January 1, 1937, only about a third of the 15,346 oil wells drilled at various times in Baku remained in operation. In the United States the figure was two thirds (year 1929).

To sum up, Western technology and equipment could not compensate for the U.S.S.R.'s lack of experience, the shortage of raw materials and of supplies, disorganization and incompetence.

Nevertheless the main thing is that the industrialization of the Soviet oil sector was carried out. Oil fields and refineries reported regularly. But Soviet history opted to keep mum about who had made the transformation possible. Even those American-style wooden cottages built to accommodate the oil workers in new settlements were passed off as exclusively Soviet ideas.

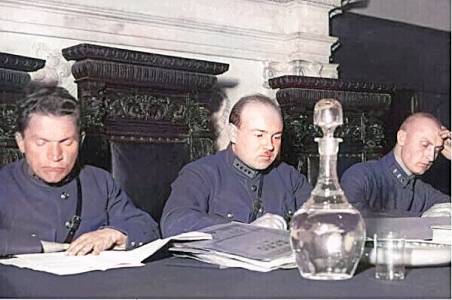

Alexander Pavlovich Serebrovsky was arrested on September 23, 1937. By a resolution of the October Plenum of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Serebrovsky was removed from the list of candidates eligible for membership in the Central Committee and was an exposed as an "enemy of the people." The formal accusation read,

Member of the anti-Soviet sabotage and terrorist center of the Right, Serebrovsky worked in the Heavy Industry department of the U.S.S.R. since 1934. As Deputy People's Commissar of Heavy Industry he performed sabotage and subversive work in the gold mining industry. In April 1937 he collaborated with a terrorist attempt on the life of Comrade Yezhov.

It is also established that Serebrovsky had been an agent provocateur of the Okhrana between 1914-17. Using the pseudonym "Engineer" as cover, he betrayed the revolutionary circle of the Kars Fortress to the tsarist police.

From 1930 onward Serebrovsky leaked a number of confidential state documents to foreign intelligence services, and kept doing so until the very day of his arrest.

On February 8, 1938, the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the U.S.S.R. sentenced Serebrovsky under Articles 58-6, 58-7, 58-8 and 58-11 of the Criminal Code of the R.S.F.S.R. to the death penalty plus the confiscation of all his personal property.

He was executed on February 10, 1938, and rehabilitated posthumously on May 19, 1956.

Russian sources. Primary: O. Bulanova's article, "How the U.S. helped the U.S.S.R. develop the oil industry of Baku in the 1920-30s" (Azer History website). Secondary: Excerpt from the Serebrovsky webpage in the Russian Wikipedia. The photograph of the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the U.S.S.R. in session comes from this article of the website, "Topography of Terror."

7. LETTER TO D. I. KURSKY.1

May 17, 1922

Comrade Kursky,Pursuant to our conversation I herewith enclose the draft of a supplementary article to the Criminal Code.2

It's a rough draft that needs editing and polishing of course, but I trust that the main idea is clear: to publicize a thesis whose principle is politically correct, legalese aside. The thesis must explain the substance, necessity, limits and justification of the use of terror.

The courts must not ban terror (that would be deception or self-deception) but spell out its motives and legalize its principle plainly, without make-believe or embellishment. The formulation must be as broad as possible because only revolutionary law and revolutionary conscience can more or less indicate the limits of application.

With communist greetings,

Lenin

VARIANT 1.

Propaganda or agitation or membership in or help provided to organizations whose object is to assist that section of the international bourgeoisie which refuses to recognize the ownership rights of the communist system (supersedes capitalism) and is striving to overthrow it by violence through foreign military intervention or by a commercial blockade, espionage or subsidies to the bourgeois press, and similar means, is an offence punishable by death. If some proof of mitigating circumstances were brought before the court the death sentence may be commuted to imprisonment or deportation.

VARIANT 2.

a) Propaganda or agitation that objectively serves the interests of that section of the international bourgeoisie which, etc., to the end.

b) Persons convicted of belonging to or of assisting such organizations, or persons who conduct activities of the aforesaid character, or whose activities bear the aforesaid character, shall be liable to the same [death] penalty.

8. TO THE WORKERS OF BAKU.

Moscow, October 6, 1922

Dear Comrades,I have just heard Comrade Serebrovsky's brief report on the situation in the Azerbaijan oilfields.1 The difficulties of the situation are by no means small.

I send you my cordial greetings and urge you to do all you can to hold on for the immediate future. Circumstances are always particularly difficult at the start, but they lighten with time. We must win and we shall do so at all costs.

Once more my most cordial communist greetings.

V. Ulyanov (Lenin)

9. TO THE SOCIETY OF FRIENDS OF SOVIET RUSSIA (IN THE UNITED STATES).

October 20, 1922

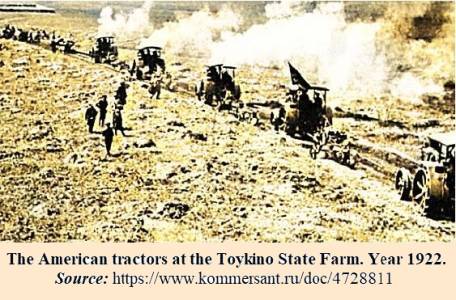

Dear Comrades,I have just verified via special inquiry to the Perm Gubernia Executive Committee the extremely favourable information published in our newspapers about the work performed by the members of your Society, headed by Harold Ware, with the tractor team at the Toikino State Farm, Perm Gubernia.

In spite of the extreme remoteness of that locality from the centre and in spite of the devastation caused by Kolchak during the Civil War you have achieved successes which must be regarded as truly outstanding.

I hasten to express my profound gratitude to you. Please publish this letter in the journal of your Society and, if possible, in the general press of the United States.

I am requesting the Presidium of the All-Russia Central Executive Committee to label this state farm a model farm and to render it special and extraordinary assistance in the construction of a repair shop and to supply it with the petrol, metal and other materials required for the job.

Once again on behalf of our Republic I express our profound gratitude to you.

Please bear in mind that no form of assistance is as timely or important for us as the one you are rendering.

Lenin

Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars

10. SPEECH AT A PLENARY SESSION OF THE MOSCOW SOVIET.1

(Stormy applause. "The Internationale" is sung)

Comrades,

I regret very much and apologize that I have not been able to come to your session earlier. As far as I know you intended a few weeks ago to give me the opportunity of addressing the Moscow Soviet. I could not come because owing to my illness I have been incapacitated (to use the professional term) for quite a long time from December onwards, and because of this reduced ability to work, I had to postpone my present address week after week.

I also had to pile a very considerable load of work on Comrade Kamenev. You will remember that I first piled it on Comrade Tsyurupa and then on Comrade Rykov. And I must say, using a simile I have previously used, that Kamenev was suddenly burdened with two loads of work, mine and his, but it should be said that the horse, to stretch the simile, has proven to be exceptionally capable and zealous.

(Applause)

All the same, however, nobody is supposed to haul two loads and I am presently waiting impatiently for Comrades Tsyurupa and Rykov to return, and we shall share the work a bit more fairly at least. As for myself, in view of my reduced ability to work, I spend much more time looking into matters than I would like.

In December 1921 I had to stop working altogether. It was year's end, we were effecting the transition to the New Economic Policy and it was already apparent then that the transition we had embarked upon at the beginning of 1921 was quite difficult, a very difficult transition, I should say. We have now been going at it for longer than eighteen months.

[...]

"The New Economic Policy"! What a strange title. It was called a "New Economic Policy" because it pointed backward in time. Presently we are retreating, going back, as it were, but only to prepare a fast track and eventually make a bigger leap forward. We do not yet know where or how we will regroup, reset and relaunch a most stubborn offensive after this retreat. But, as the proverb says, we must look not ten but a hundred times before we leap, in order to cope with the incredible difficulties that mar all our tasks and problems.

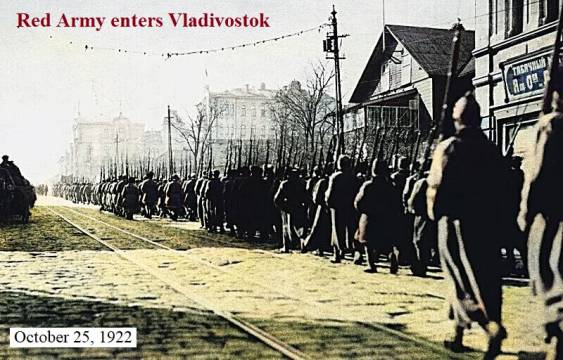

You know perfectly well what sacrifices were made to achieve what has been achieved; you know how long the Civil War dragged on and what effort it cost. Well now, the capture of Vladivostok has demonstrated to us all (for though Vladivostok is a long way off it is one of our own towns after all)...

(Prolonged applause)

... everybody's desire to unite with us and with our achievements.2

Now the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic stretches from here [Moscow] to there [Vladivostok]. This desire to join has rid us both of our civil enemies and of the foreign enemies who attacked us, I am referring to Japan.

[...]

11. TO THE PRESIDIUM OF THE FIFTH ALL-RUSSIA CONGRESS OF THE SOVIET EMPLOYEES' UNION.1

November 22, 1922

Dear Comrades,The primary immediate task of the present day and for the next few years is to reduce the size and cost of the Soviet machinery of state systematically by reducing staffs, improving organization, eliminating red tape and bureaucracy and restricting unproductive expenditure. Your union has a great deal of work to do in this sphere.

Wishing the Fifth All-Russia Congress of the Soviet Employees' Union success and fruitful work I hope that it will especially deal with the question of the Soviet machinery of state.

V. Ulyanov (Lenin)

Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars

12. NOTES ON THE TASKS OF OUR DELEGATION AT THE HAGUE.1

On the question of combating the danger of war, to be discussed in the Conference at The Hague, I venture that the greatest difficulty lies in overcoming the prejudice that this is a simple clear and comparatively easy question.

"We shall retaliate to war with a strike or a revolution" is what all prominent reformist leaders usually say to the working class. And very often the seemingly radical nature of their proposed measures satisfies and appeases the workers, co-operators and peasants.

Perhaps the best alternative is to start with the sharpest refutation of this opinion; to declare that particularly now, after the recent war, only the most foolish or utterly dishonest people can assert that such a strategy for combating war is of any use; to declare that it is impossible to "retaliate" to war with a strike, just as it is impossible to "retaliate" to war with a revolution in the simple and literal sense of those terms.

We must explain to people the reality of war, show them that it's hatched in the greatest secrecy and that ordinary workers' organizations, even if they call themselves revolutionary, are utterly helpless in the face of a truly impending war.

We must explain to the people again and again, in the most concrete manner possible, how matters stood in the last war and why they could not have stood otherwise.

We must take special pains to explain that the "defence of the fatherland" ploy will inevitably surface and that the overwhelming majority of working people will invariably respond pro their bourgeoisie.

Therefore it's necessary first to explain what "defence of the fatherland" really means. As a corollary it's necessary, second, to explain what "defeatism" means. Lastly we must explain that the only possible way to combat war is to preserve existing organizations (and start illegal ones) whose revolutionaries, experienced in warfare, unroll prolonged anti-war activities. All this must be brought to the front.

"Boycott war!" That's a silly catch-phrase. Communists must take part in every war, even the most reactionary.

Examples from pre-war German literature, say, and in particular from the Basle Congress of 1912 should be presented as especially concrete proof that a theoretical admission that war is criminal, that socialists cannot condone war, etc., turn out to be empty phrases because there is nothing concrete in them. The masses are not given a truly vivid representation of how war might and will creep up on them. On the contrary the dominant press, with its infinite number of copies, obscures this socialist stance daily and weaves such lies around it that the feeble socialist press is left absolutely impotent, the more so when even during peacetime it propounds fundamentally erroneous views of this issue. In all probability the communist press of most countries will also disgrace itself.

I think that our delegates at the International Congress of Co-operators and Trade Unionists should assign tasks themselves and expose all the sophistries being currently advanced as a justification for war. These sophistries are perhaps the principal means employed by the bourgeois press to rally the masses in support of war; and the main reason why we are so impotent is because we do not expose their sophistries before the event or, still worse, waive them aside in the spirit of the Basle Manifesto of 1912 with cheap boastful and utterly empty vows that we won't let war break out, that we fully acknowledge that war is a crime, etc.

[...]

13. BETTER FEWER, BUT BETTER.

[...]

The conclusions to be drawn from the above are the following: we must make the Workers' and Peasants' Inspection a really exemplary institution, a tool for improving our state apparatus.1

In order for it to reach its desired high level we must follow the rule, "Measure your cloth seven times before you cut."

We must utilize the very best of our social system for this purpose and utilize it with the greatest caution, thoughtfulness and knowledge, to build up the new People's Commissariat. The best elements of our social system are, first, the advanced workers, second, the truly enlightened elements who won't take word for deed and won't utter a single word that goes against their conscience. They should not shrink from admitting difficulties or from struggling to reach their objective.

We have been bustling for five years trying to improve our state apparatus, but it has been mere bustle which has proven useless or even futile or even harmful. This bustle gave the impression that we were doing something, but in effect it was only clogging up our institutions and our brains.

It's high time things changed.

We must follow the rule: Better fewer, but better.

We must follow the rule: Better to get good human material in two or even three years than to work in haste without the hope of getting any at all.

I know that it will be hard to stick to this rule and apply it in our circumstances. I know that the obverse will wriggle its way in through a thousand loopholes. I know that enormous resistance and devilish persistence will be required, that toil in this field will be hellishly hard in the first few years at least. Nevertheless I am convinced that only with such effort shall we be able to reach our goal and create a republic really worthy of the name Soviet, socialist, and so on, and so forth.

In substance the matter is the following: Either we presently prove that we have really learned something about state organization (we ought to have learned something in five years) or we show that we are not mature enough for it. If the latter is true we'd better not tackle the task at all.

[...]

We ought to open a contest at once to compile two or more textbooks on the organization of labour in general and management in particular.

We can take as a basis the book already published by Yermansky (photograph on the left) although it should be said in parentheses that he obviously sympathizes with Menshevism and is unfit to compile textbooks for the Soviet system.2

We can also take for basis the recent book by Kerzhentsev (photograph on the right) and some other partial textbooks available may be useful too.3

We ought to send several qualified and conscientious people to Germany or to Britain to collect literature and study this question. I mention Britain in case it is found impossible to send people to the U.S.A. or Canada.

[...]

We must strive to build a state where the workers retain the leadership and confidence of the peasants, and by exercising the greatest economy remove every trace of extravagance from our social relationships.

We must reduce our state apparatus to the utmost degree of thrift. We must banish all traces of extravagance, so much of which has been left over from tsarist Russia, from its bureaucratic capitalist state machine.4

Will this not be a reign of peasant limitations?

No. If we see to it that the working class retains its leadership over the peasantry we shall be able, exercising the greatest possible thrift in the economic life of our state, to use every savings we make to develop our large-scale machine industry, to develop electrification, the hydraulic extraction of peat, to complete the Volkhov Power Project, etc.5

In this and this alone lies our hope. Only when we accomplish this shall we be able to switch horses, speaking figuratively, from the peasant muzhik horse of poverty, the economic horse of a ruined peasant country, to the horse the proletariat seeks and must seek, the horse of large-scale industry, electrification, Volkhov Power Station, etc.

That's how I conflate in my mind our general plan of work, policy, tactics and strategy with the functions of a reorganized Workers' and Peasants' Inspection. This is what justifies in my opinion the exceptional care and attention we must devote to the Workers' and Peasants' Inspection, raising it to an exceptionally high level, lending it a leading role with Central Committee rights, etc., etc.

And the justification is that only by purging our government machine thoroughly, by shrinking to the utmost what is not absolutely essential can we keep moving forward with some certainty. Moreover we will do so not like a small-peasant country under ubiquitous limitations but on a road leading us to large-scale industry.

These are the lofty goals I envision for our Workers' and Peasants' Inspection. That's why I imagine it in the future as an "ordinary" People's Commissariat spliced with the highest authority of the Party [the Central Committee].

March 2, 1923

We see prevailing among us now a regular riot, an orgy, of all kinds of fêtes, celebration meetings, jubilees, unveiling of monuments and the like. Scores and hundreds of thousands of rubles are squandered on these "affairs." There is such a crowd of celebrities of all kinds to be fêted and such a multitude of lovers of celebrations, so staggering a readiness to celebrate every kind of anniversary—semi-annual, annual, biennial and so on—that truly tens of millions of rubles are needed to satisfy the demand.

Comrades, we must put a stop to this profligacy unworthy of Communists. It is high time to understand that with the needs of industry to provide for, and faced with such facts as the mass of unemployed and of homeless children, we cannot tolerate and have no right to tolerate this profligacy and this orgy of squandering.

(J. V. Stalin. Works, 8, in The Economic Situation of the Soviet Union and Party policy, pp. 141-2)

14. THE FOREIGN INTERVENTION DRAWS TO A CLOSE.

Madrid: A British steamboat left the port of Marseille with a cargo of beans and other cereals destined for the starving population of Russia.